Responses to migrants’ needs while transitioning through borders

For this report, this stage includes short-term stays in a country or at a border, with the intention of quickly continuing the journey. The section presents an overview of migrants’ needs while they transition across borders, as well as six smart practices that address some of these needs.

Key messages of this section

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

- When travelling, and particularly when transitioning across international borders, a vulnerable migrant is likely to need support in most dimensions of resilience. The needs include: regulatory safety, financial resources, physical support, information, and maintaining family links. The needs are often urgent and temporary.

SMART PRACTICES

- Most smart practices identified provide physical support and practical information.

- The smart practices identified have a few characteristics in common. They provide short-term solutions (with one exception), and most are: flexible and dynamic; do not necessarily engage migrants in the solutions (but rather provide solutions directly); are targeted initiatives; and work in partnership with local and international actors.

- When addressing the needs of migrants in transit, actors have faced a few common challenges. These include: constantly changing dynamics that result in services and information quickly becoming obsolete, lack of awareness among migrants about the existence of services, challenges to convince the authorities to allow National Societies to support irregular migrants or monitor the impact of services, and balancing the provision of services to migrants and the needs of local populations. Some lessons learned are that: it can be helpful to use a range of distribution/awareness-raising mechanisms; it is ideal to have migrants engage in peer-to-peer sharing; authorities may be willing to allow the provision of services in exchange for numbers on irregular migrants receiving support in their area; it is important to make services available to local populations to increase acceptance; and it is important to have strong collaboration with government and other stakeholders.

Migrants are likely to need support across most of the dimensions of resilience

When travelling, and particularly when transitioning across international borders, a vulnerable migrant is likely to need support across most of the dimensions of resilience. Needs include: regulatory safety, financial resources, physical support, information and maintaining family links. These needs are often urgent and temporary.

Governance/regulatory systems. When crossing a border, a migrant needs to know that she or he can continue on the intended route safely, without facing the risk of being detained or returned. When regulatory safety is not guaranteed, she or he may be forced to take an alternative route. The alternative route might be longer, or more dangerous and can expose him or her to additional threats, such as crime and violence, exposure to harsh weather conditions, or other unsafe conditions.

Financial capital. Under the best scenario, the migrant has sufficient financial resources to provide for his or her (and his or her family’s) needs during the journey. However, this is often not the case for vulnerable migrants. If the migrant has some savings, these can be rapidly depleted as he or she proceeds (or cautiously saved for the unknowns ahead). The financial situation of a vulnerable migrant is particularly sensitive because of the uncertainty of when she or he will have a stable source of financial income again. While travelling, it is very difficult for the migrant to find sources of income. To earn, she or he will need to pause the journey for a period to seek income opportunities.

Physical capital. While travelling, a vulnerable migrant can normally not carry too many essentials, such as a tent, food supplies, etc. If this is coupled with limited financial resources, it can result in undesirable physical exposure to threats and dangers. The migrant will hence often need access to temporary shelter, water and sanitary facilities. She or he is likely also to need access to warm and nutritious food as well as opportunities to replenish food supplies. Food should be lightweight and adequate to meet his or her cultural and religious restrictions. Depending on the road taken, the financial resources, and other aspects such as weather conditions or safety along the path, she or he may also need access to health care. Health care needs may range from first aid and emergency health care; from primary health care to treatment for undernutrition, dehydration, or hypothermia; from surgery for a broken limb to delivery of a new-born child. Moreover, the migrant may have a chronic disease such as diabetes, and require replenishment of treatments.

The migrant may be escaping a traumatic situation or may have had traumatic experiences on the journey. Psychosocial support might be important during the journey as well. However, at this stage the migrant is often determined on moving ahead and may not feel she or he has sufficient time to receive psychosocial support. Moreover, psychosocial support often requires a certain level of trust with the psychosocial assistant, which is difficult to develop in the short-time frame that migrants are in a given area. As with all other needs, the importance of psychosocial support increases dramatically for unaccompanied children, victims of abuse, and other vulnerable groups.

Human capital. Up-to-date information for the journey is essential. The migrant will need an overall and up-to-date understanding of his or her rights across intended transit countries and in the country of destination, particularly if there have been changes since he or she started the journey. Practical information on the safest route to the next border, safety measures, etc., is also essential. While education is important, it is often a secondary priority while travelling.

Social capital. While migrants are moving, it might become more and more difficult for them to maintain links with family members that are not travelling with them. For example, as they cross the borders, they may no longer have a working telephone or access to internet to contact their families. They might also have been separated from their families during the trip. For example, they might have had to take different buses or boats, and not know where the rest of the family got off the bus or landed. While migrants need to be respected by the societies through which they travel, given the temporary nature of their presence, social integration with the host community is not an essential need at this stage.

Natural capital. As discussed earlier, lack of natural capital (poor quality of atmosphere, biodiversity, water, land and forest) may have been a driver of migration, and should have been addressed as part of initiatives for vulnerable populations. However, the need for natural capital is no longer essential once a person migrates across borders, given the temporary nature of their stay in any given place.

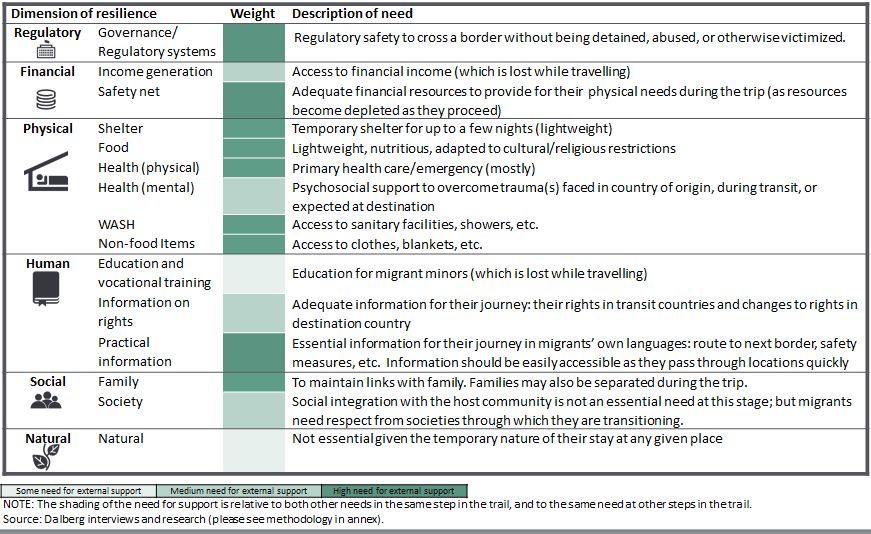

The table below provides a high-level summary of the key needs of migrants as they start their international journey. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for governance/regulatory systems

PALESTINIAN REFUGEES, LEAVING LEBANON

Closure of borders forces migrants to take more dangerous routes. A Palestinian woman living in Beirut whose husband migrated to Europe explained that, following the closure of many borders, he had been forced to take the sea route.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Lack of proper documentation forces migrants to take additional risks. A young Congolese man shared his story: his family paid the driver of a goods truck and lay under the goods in the truck to attempt to cross a border. They were extremely lucky. Soldiers pierced the goods with knives to make sure that no humans were hiding among them, and narrowly missed where the family was.

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Risk of detention pushes migrants to take more dangerous routes. Returned Honduran migrants explained that the route they follow is to go north from Honduras, into Guatemala, then Mexico and then the US. There are many ways to get to the US though Mexico. Crossing Guatemala is simple: they are legal there and can cross it within a day. However, in Mexico they are irregular. They explained that the traditional routes do not work anymore, as they are known to the authorities. Instead, they use other routes that are more dangerous. To cross through Mexico and into the US, they usually pay smugglers, knows as coyotes. “It’s expensive (between 3,000 and 10,000 US dollars), the one good thing is that there is always people helping. Coyotes are the guides that know the routes and have the connection to try to get you to the US.”

MIGRANTS FROM MYANMAR, THAILAND

Risk of detention pushes migrants to take more dangerous routes. Labour migrants from Myanmar in Thailand explained that, because they were afraid of being caught while migrating, they travelled for two days and two nights, sleeping in the woods, and walking only in the night time. “Walking through the jungle is very difficult,” they explained.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits. (NOTE. interviews with migrants from Myanmar were conducted by a local consultant with support from IFRC CCST Bangkok as part of a different study.)

Examples of the need for financial and physical capital

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, EUROPE

Migrating through harsh climatic conditions physically exposes migrants to hardship during the journey. Staff from a European National Society explained that migrants crossing European borders during the winter were in much worse physical condition than those crossing in spring/summer.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Migrants with limited financial resources are exposed to hardship and abuse along the trail. For example, a young Congolese man and his family managed to find a truck for part of the way. However, after the truck, they had to walk for days with nothing to eat on the way. To get onto a final bus, his mother had to pay everything she had. At many borders, he believes his mother had to offer sexual favours to the border security so they be allowed to cross. “She went inside and when she came back out I could see that everything was not okay. She was very sad. It was as if she had done things she didn’t want to do.” Other Congolese migrants we spoke to in Kenya confirmed that they received no support at origin or along the way, and that they experienced many instances of abuse (extracting money or sexual abuse) on the way to get from country to country.

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Migrants with limited financial resources are exposed to hardship and abuse along the trail. In Honduras, they explained that they faced “the usual needs about where to sleep, where to eat, security, and others, but they are all risks we are aware of”. “We sleep anywhere: streets, jungle, wherever we are when its gets dark.” Some valued the availability of shelters (“In Veracruz (city of Mexico) there is so much food, everyone helps you, there is even a shelter for migrants where you can spend the night”), while others explained that, due to the hurry to move, they did not always have time to find appropriate shelter. “To be honest, we are on hurry, all we want is to get to the US, so we try to move as fast as possible and don´t waste time looking for where to sleep or for a job on the way.” Others shared additional hardships experienced during the journey. “I have seen women run out of water, and whoever is left behind then is left behind.” “In the borders nobody helps you, each man [is] alone.” “Everything cost money, getting people to the US illegally is a business.” “Many of us get robbed on the route, but you have to keep going.”

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits, and interviews with staff from National Societies.

Examples of the need for physical, human (information) and social (family links) capitals

ETHIOPIAN MIGRANTS, KENYA

Lack of safe transport options forces migrants to take dangerous and hard routes. Ethiopian migrants in Kenya shared that the key issue when fleeing was transport. Many had to endure a difficult one week walk. Many passed away during the journey because the conditions were too difficult.

MIGRANTS FROM MYANMAR, THAILAND

Female migrants can easily be exposed to abuse during the journey. “Most problems we encountered were being sexually harassed and raped, arrested and jailed. Many times we were in a crisis situation and did not know who we should ask for help, where and how,” explained female migrants from Myanmar about their journey.

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Some migrants access information from friends or smugglers. Returned Honduran migrants explained that they “know about the routes from mouth-to-mouth; there are so many different ones that everyone knows some of them, and have their preferences (each one has its own risks).” One of the interviewees mentioned he had seen informational messages, which were a good reminder, even though most of the information they need is either provided by the coyote or by someone who has already done the journey before.

Some migrants were able to maintain family contacts through the local churches. “To call home you just go to a church, and they will help,” explained Honduran migrants.

MONGOLAN MIGRANTS, SWEDEN

Some migrants rely completely on traffickers to gather information and organize their journey. Some Mongolian migrants in Sweden explained that they had paid a trafficker 3,500 Euros. He arranged everything for them to get there. They were transported in a caravan that took them to Sweden.

Other migrants need less information during the journey, as they fly in legally on a temporary visa. Other Mongolian migrants explained that they had come into Europe by plane, on a temporary visa (for example to attend a conference), and had simply not returned.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits (NOTE. interviews with migrants from Myanmar were conducted by a local consultant with support from IFRC CCST Bangkok as part of a different study).

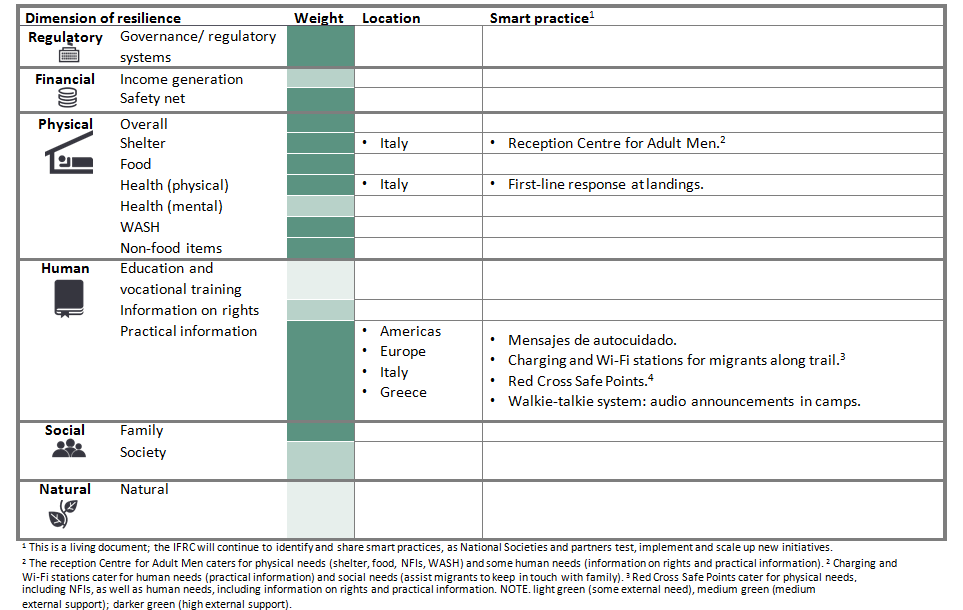

Most smart practices identified provide physical support and practical information

Smart practices identified at this stage are provided in the table below.

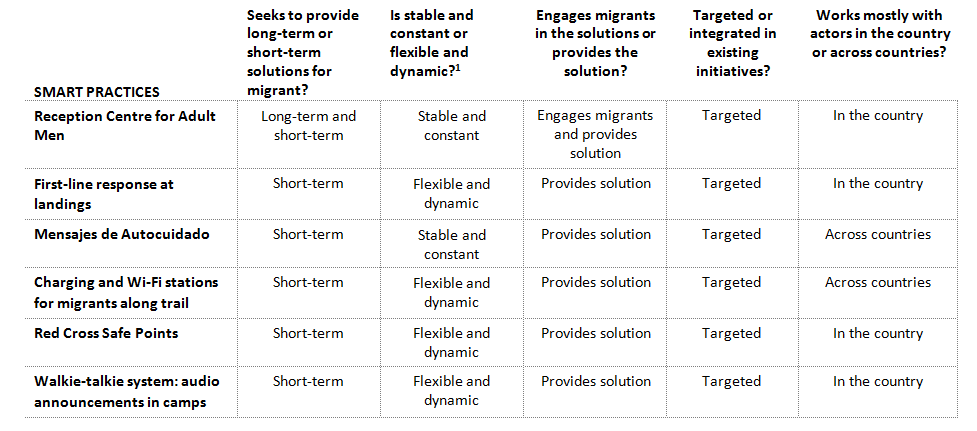

Common characteristics of smart practices

The smart practices identified during transition across borders have several common characteristics. With one exception, they seek to provide short-term solutions for migrants. In addition, most are flexible and dynamic to address varying flows and needs of migrants; do not necessarily need to engage migrants in the solutions; are targeted initiatives that focus on the needs of migrants, and do not easily piggy-back existing humanitarian outreach initiatives in the community; and work in partnership with local and international actors.

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

Common challenges

The constantly changing dynamics at this stage mean that information quickly becomes outdated or that services placed along the trails (such as Wi-Fi stations) are no longer needed.

Lessons learned

The design of information should be minimalistic to reduce data requirements.

Low technology options can contribute cheap and effective solutions.

Common challenges

There is a lack of awareness amongst migrants about the existence of services.

Lessons learned

It can be helpful to use a range of distribution/awareness-raising mechanisms, including broad radio broadcasting, social media, and low technology options. It is ideal to have migrants engage in peer-to-peer sharing.

Common challenges

It can be challenging to convince the authorities to allow a National Society to provide services which are predominantly for irregular migrants.

Lessons learned

It is important for local branches to know the territory well and collaborate closely with government and other stakeholders.

Common challenges

Monitoring the impact of services can be difficult as populations move quickly.

Lessons learned

Develop beneficiary feedback surveys at a different stage of the trail.

Common challenges

It can be difficult to balance the provision of services to migrants and the needs of local populations (to avoid creating the perception that migrants are favoured and generating hostility towards migrants).

Lessons learned

It is important to make services available to locals in order to build acceptance.

Common challenges

Due to xenophobia in the transition community, sometimes volunteers are treated badly as it is frowned upon to help migrants.

Lessons learned

One way to help volunteers is to provide psychosocial training and support.

Common challenges

Language is often a barrier to provide and receive the right information and support, as volunteers do not necessarily speak the language of the migrants.

Lessons learned

Provide materials for migrants in several languages. Keep different cultural preferences in mind when designing interventions.

Develop a volunteer migration toolkit in multiple languages which includes the most common questions migrants have and answers to them.

Common challenges

Physical and psychosocial support is very important for victims of conflict, human trafficking, and abuse, and unaccompanied minors. However, at the borders, because of the fast pace and sometimes undercover nature of the transit, it becomes extremely difficult to identify and thus support particularly vulnerable groups.

It is also difficult to identify and provide support to particularly vulnerable migrants, as people often do not stay for sufficient time.

Lessons learned

Lesson learned not identified by the study.

Common challenges

Common challenge not identified by the study.

Lessons learned

A good network and collaboration with key local actors (governments, NGOs, donors, other relevant actors) is a fundamental element for effective implementation of services.

Smart practices archive: Border