Responses to migrants’ needs during long-term stays in a country of destination

For this report, this stage considers migrants who live in a country for a long period with the intention of remaining indefinitely, with the intention of potentially migrating elsewhere, or with the intention of returning home. The following section presents an overview of the needs of migrants when they integrate in a country of destination and 25 smart practices that address some of those needs.

Key messages of this section

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

- When a migrant arrives in the country where s/he intends to stay for a long period (indefinitely, or until s/he moves to a third country, or until s/he returns home), a number of needs emerge. While migrants will aim to provide for their own needs, this might be challenging due to a combination of factors, such as the legal status of their stay, their access to rights, etc. Hence, for most needs, the best solutions enable them to be self-sufficient.

SMART PRACTICES

- A large number of smart practices were identified across most dimensions.

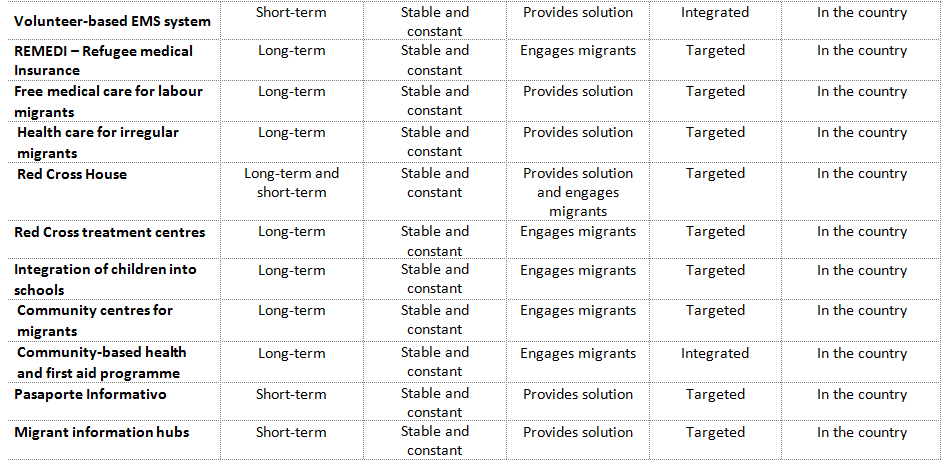

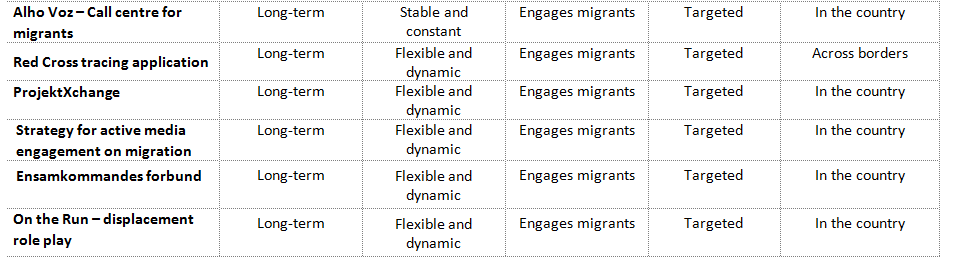

- The smart practices identified have several characteristics in common. Most provide long-term solutions; are stable and constant; tend to engage migrants in the solutions; are targeted; and work in partnership, mostly with actors in the country.

- When addressing the needs of migrants, actors have faced a number of common challenges. These include: services can act as pull factors within a country, language barriers can hamper provision of services, vulnerable host communities may perceive that they receive less support than migrants, and it is difficult to identify and retain staff and volunteers. Some lessons learned are to have clear and fast scale up plans, to engage the host community in services, and to widely advertise for volunteers.

To remain resilient, migrants need regulatory safety, income, healthcare and social capital

When a migrant arrives in a country where s/he intends to stay for a longer period (indefinitely, until s/he moves to a third country, or until s/he returns home), a number of needs emerge. While migrants will aim to provide for their own needs, this might be challenging due to a combination of factors, such as the legal status of their stay, their access to rights, etc. Hence, for most needs, the best solutions enable them to be self-sufficient.

Governance/regulatory systems. Throughout his/her stay, a migrant needs to be able to remain in the country as long as needed or agreed. Similarly, s/he needs to be able to leave it safely when desired. During his/her stay, the migrant also needs to have access to housing, food, healthcare, education and employment opportunities.1

Financial capital. Particularly important for long term stays is access to safe employment or income generating opportunities.Access to safe employment opportunities will allow migrants to become self-sufficient, and regain the dignity they may feel they lost during their journey. One of the interviewees clearly expressed this need: “I have high education, I had a job. I don’t need handouts, others may need help more than me. What I need is a job so that I can provide for my own needs and those of my children.” Language barriers, lack of adequate certificates, or lack of work permits may all impede migrants from finding adequate employment. Even when they get a job, they may face unfair treatment, such as general discrimination in recruitment, lower salaries, longer hours, physical punishments, etc.

Physical capital. As the migrant settles into the new country, s/he will often try to find his or her own provisions for housing and food. Even if the migrant is able to provide for his/her own physical needs, s/he might still need legal or translation support to access rights fully (e.g., to avoid abusive rents by house tenants, or to explain health needs to a doctor). It is worth noting, however, that, even when a migrant has a job or access to financial income, salaries are often lower. As a result, housing, food, access to healthcare, etc. can be precarious. For example, a domestic worker may live at the employer’s house, where s/he may have very limited privacy. Other migrants may need to rent a room to share with a large family (if they rely on one bread winner only).

In cases where the migrant (or his/her family members) cannot find a job, or the salary is insufficient, s/he needs to rely on assistance for shelter, food, etc. While many migrants find some shelter solutions, access to health care (both physical and mental) can be more complex, particularly if their irregular status impedes them from accessing free public services, or if they need to pay for services. As physical needs are covered, the need for psychosocial support increases in importance. The migrant will be ready to start overcoming the traumas escaped from or experienced during the journey. S/he may also have had time to develop a stronger trust relationship with the psychosocial supporter, which will facilitate psychosocial support.

Human capital. Children, youth and some adults need access to primary education, secondary education, higher education and vocational training. This might be challenging if migrants are irregular or if they need to pay for education. Language may also be a barrier, which may cause delays in children’s education. Overall, the migrant will also need access to up-to-date information on his/her rights and relevant changes in regulation, as well as practical information on how to access these rights. Language may again be a barrier to accessing adequate and up-to-date information through the ordinary means available to citizens (news, radio, etc.).1

Social capital. At this stage, migrants can seek to re-establish broken links with family and re-unite with family members. The migrant also needs to feel part of the new community. Language and diverse cultural norms may however be barriers to full integration. While integrating in the new society, s/he also needs to keep a sense of belonging to the country of origin, particularly if the migrant plans to return. For example, his/her children need to learn the language, cultural norms, etc., if they are one day to return to their home country. Access to religious services is also important to many migrants. Migrant networks and migrant associations are important social spaces too. Through migrant associations, migrants can feel valued again and can use their existing capitals to support fellow migrants.

Natural capital. The need for natural capital is more important again, given the long-term intended stay in the country. Migrants may need high quality land and water to grow crops, rely on forests or lakes for fishing and water, etc. (It is worth noting, however, that, for this report, no initiatives were found that address natural capital in the host community, with the migrant in mind.)

1 Access to education and employment opportunities might include by means of legislative recognition of previous studies and skills.

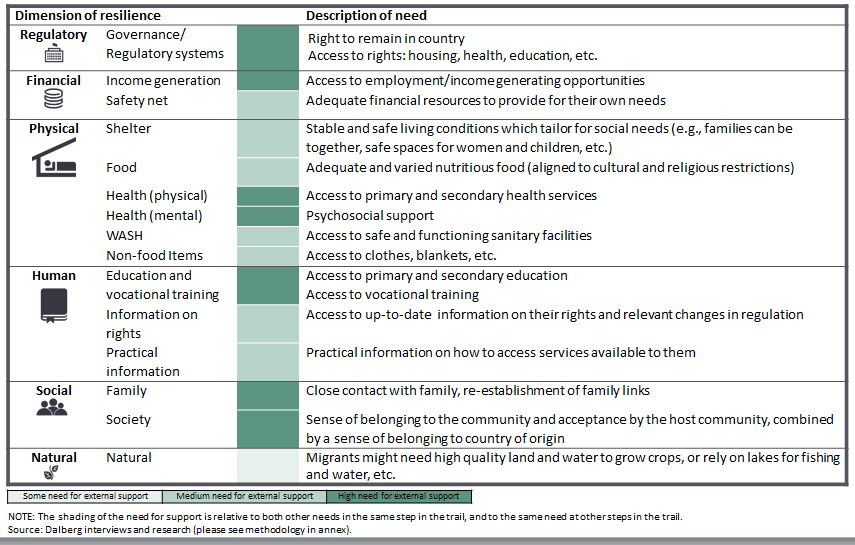

The table below provides a high-level summary of the common needs for external support that migrants may have. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for governance/regulatory systems

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

In some situations, some migrants have direct access to several basic services. In Turkey, all Syrian migrants have the right to free education and health care.

MONGOLIAN MIGRANTS, SWEDEN

When they are irregular, migrants often fear being detained. Mongolian irregular migrants explained that they live in constant fear and trauma because of the threat of deportation. The fear of being deported was especially burdensome for some. For example, one interviewee said “I’m not happy because I am undocumented”, whereas another said that she was “100% happy” even though she was undocumented.

ECONOMIC MIGRANTS, QATAR

In some situations, even if there is a legal framework to protect migrants, it is not respected by employers. An interviewee explained that in Qatar, the legal framework forbids employers to remove a migrant’s passport. However, this seems to be a fairly common practice. Ministerial Decree 16/2007 forbids outdoor work between 11.30am and 3pm in the summer. It also states that no labourer may log more than 5 hours of work in the morning. These too are unfortunately common practices. A situation of dependency on the employer can lead to abuse by the employer, who may limit a migrant’s social interaction with the external world, or sexually or physically abuse him or her, etc.

ETHIOPIAN AND ERITREAN MIGRANTS, KENYA

When they are irregular, migrants often fear being detained. Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants explained that, given their irregular status, most of them were changing residential area from week to week to avoid getting caught

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits, or phone interviews with actors in the country.

Examples of the need for governance/regulatory systems, and financial and physical capital

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

Limited financial resources force migrants to live in dire situations. A Syrian woman, with a family of nine, had been lucky. A Turkish neighbour had offered her family his empty apartment free of rent. She only needed to pay for electricity and water. However, there was an unpaid water bill from a previous tenant of several hundreds of dollars, which she could not afford to pay. Her family has one breadwinner, who earns a minimum salary. Her apartment is hence without water. Every day she walks several kilometres to bring water to her family.

MIGRANTS FROM MYANMAR, THAILAND

For many, regulating their status is a key priority. Several migrants from Myanmar said that obtaining an ID card was one of their key priorities. One female migrant explained that she wanted her two children to have an identity card because she did not want her children to face any difficulties “so that both can have access to better education and work, and access to the basic welfare of Thailand”.

SOMALIAN MIGRANTS, KENYA

Female migrants may be more exposed to harassment and abuse. A single Somalian lady shared that she faces harassment from all sides, including from males in the community. A Somalian shop owner confirmed that he regularly witnesses sexual assaults on women in the community.

MONGOLIAN MIGRANTS, SWEDEN

The irregular status of migrants may force them to take on lower paid jobs and suffer abuse. Mongolian migrants in Sweden explained that their employers often exploited their situation as irregular migrants to offer them sub market rates. They explained that complaining to their employers did not help as they were told that they could leave because “nobody cares about you, and I can call and have you deported”. If they try to object too much, they get fired. They also explained that because they only have an oral contract, employers frequently fail to pay them.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits. (NOTE. interviews with migrants from Myanmar were conducted by a local consultant with support from IFRC CCST Bangkok as part of a different study.)

Examples of the need for governance/regulatory systems, and human and financial capital

MINOR MIGRANTS, CENTRAL AMERICA

The irregular status of migrants may make them more dependent on the will of their employer and more exposed to abuse. A study by UNICEF, ILO and IOM on child migrants in Central America highlighted that in many cases young labour migrants are not covered by their contracts, since these consider them adults, removing the possibility of holding the employers accountable. In other cases, migrants have no contract at all, even if they work directly with an employer and are at their disposal.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

The irregular status of migrants may force them to take on lower paid jobs and suffer abuse. A young man (of 19) shared that he had arrived with his mother and siblings in 2012 with nothing. A ‘good Samaritan’ who was from the same tribe in Congo took them into her home where she offered them a place to sleep and a little money. His mother eventually disappeared, after he had heard her say that “she was tired of living”. With his mother gone, he had to start working to help the ‘good Samaritan’ to look after him and his three siblings. He finds work washing cars and carrying goods for 50 Kenyan shillings (50 US cents) a day.

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

Lack of language skills or certificates can create obstacles to finding jobs. Several Syrian migrants in Turkey explained that most were struggling to find stable jobs, and relied on temporary jobs, savings or loans from friends. Moreover, several interviewees shared that they were often offered much lower salaries than the locals, and were expected to work longer hours. Some specific stories are provided below:

- A Syrian woman had been a teacher in her home country. While she was eager to find a job and had submitted several applications she had not found a job. She did not speak Turkish, and lacked the national certificate required to work at national schools. She was studying Turkish in order to pass the national exam, in hope of finding a job in the future.

- A Syrian man of 50 shared his frustration that he had tried to find a job to provide for his family. However, he could not find anything, as he was considered too old. His son, 15, had found a job and was the sole breadwinner of the family. He wished that things were different and that his son could finish his education instead of having to work to provide for his family.

- A Syrian man had been living in Turkey with his family for over a year, and had yet not found a job. While initially he had relied on the few savings he had brought, he now relied on handouts from the government and Turkish neighbours, or loans from family and friends. He did not know why he was not being offered jobs.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits; IOM, UNICEF, ILO, Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes Migrantes América Central y México (2013).

Examples of the need for physical and social capital

MIGRANTS FROM MYANMAR, THAILAND

Limited funds force migrants to live in dire circumstances. Most migrants from Myanmar explained that they either lived at construction camps, or rented a room where other migrants or poor Thai people also lived. “It’s cheap but poor quality,” explained one migrant.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

The traumas experienced during the journey may lead to need for psychosocial support. Congolese migrants explained that psychosocial support against trauma is needed for both children and adults. “For kids, seeing parents struggle is difficult.” Moreover, they explained that many women live with post-traumatic stress syndrome after sexual assaults.

Because of their irregular status, some migrants cannot access health care services. Moreover, because of their irregular status, they have no access to health care. They explained how this was particularly difficult for single mothers, who did not have access to medical support during childbirth.

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

Migration often results in separated families, who may spend years without seeing each other. A Syrian woman, currently living in Ankara, Turkey, explained that her 10 year old son was in Europe, with an uncle. She had sent him there trying to find a better life for him. She wanted to reunite with him, but had not been allowed to.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits. (NOTE. interviews with migrants from Myanmar were conducted by a local consultant with support from IFRC CCST Bangkok as part of a different study.)

Examples of the need for human and financial capital

ETHIOPIAN AND ERITREAN MIGRANTS, KENYA

Some migrants shared that they would benefit from a single location where they could find out about the various services available to them. A group of Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants said that they knew of no location that would point them to where they could find different types of support, and thought such a service would be useful.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Lack of financial resources may lead to inability to pay for education. Congolese migrants explained that, in the past, education was provided by an NGO. However, the NGO no longer had sufficient funds to provide education. Some education was provided by another organization that, in an attempt to reach more students, had classes of 100 students. They explained that the classes were too large for students to hear the teachers. A young man (of 19) shared that, when he arrived in 2012, he had enrolled in class 5 for one year. After that, they could no longer afford the payments for his schooling.

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

Even when services are provided, existing systems may not be sufficient to cover all the needs. Turkey provides free classes for children at school age both at camps and in cities. Classes follow the Syrian curriculum and are taught by Syrian teachers during the afternoons, in Turkish schools. However, the schools do not have the capacity required for all Syrian children in Turkey (800,000). Several mothers worried about the education of their children.

Lack of language skills can result in obstacles for migrants to continue their education in a new location. A few Syrian girls living in Turkey had been studying at university when they had to escape the conflict. Their studies had been paused for a few years, as they did not speak Turkish, and could therefore not continue their education at the Turkish University. They did not have enough financial resources to have internet at home either, so remote online courses were therefore not an option for them. They were all studying Turkish, hoping to be able to continue their education in the future.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits.

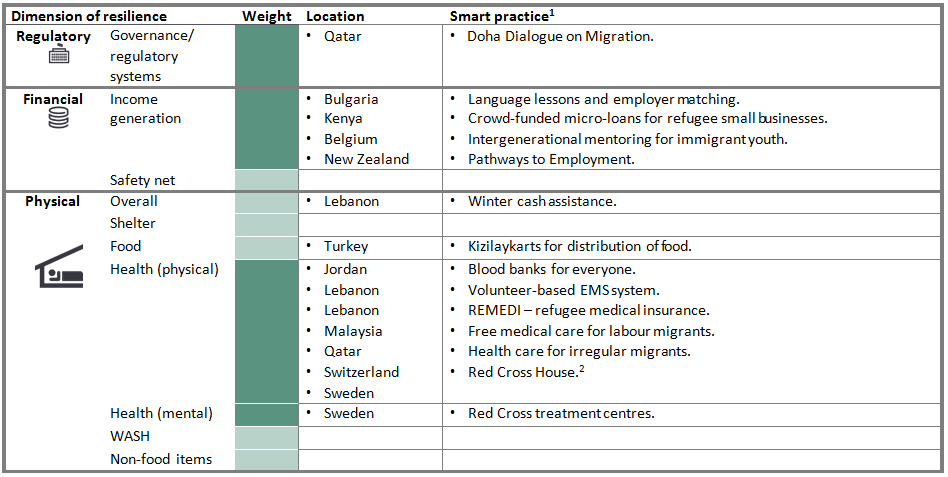

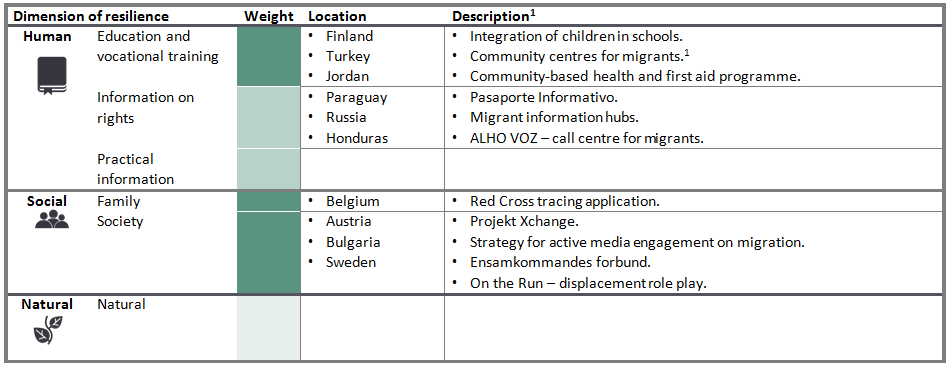

A large number of smart practices were identified across most dimensions

Smart practices identified at this stage are provided in the tables below.

1: This is a living document; the IFRC will continue to identify and share smart practices, as National Societies and partners test, implement and scale up new initiatives.

2 Caters to physical needs (food, health, WASH, NFIs), human needs (education and vocational training, information on rights, practical information) and social needs (society).

NOTE: light green (some external need), medium green (medium external support), darker green (high external support).

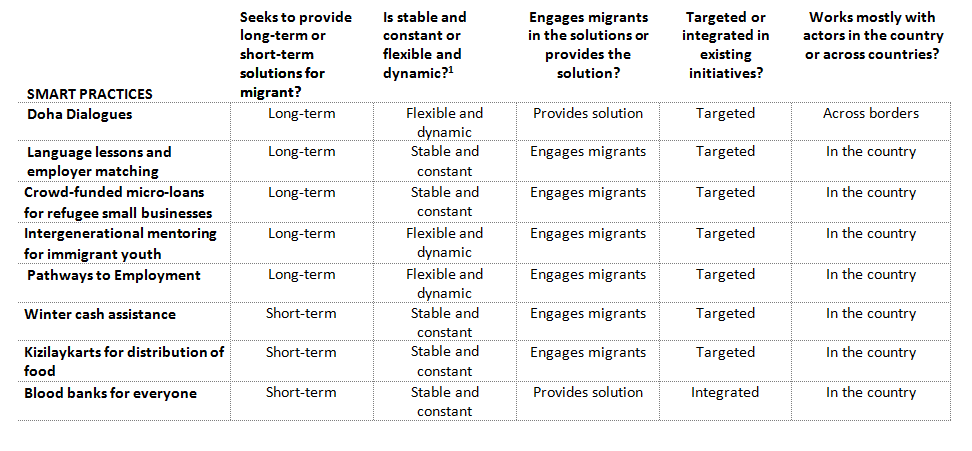

Common characteristics of smart practices

The smart practices identified have several common characteristics. Most seek to provide long-term solutions for migrants, with the vision that migrants may remain for several years; are stable and constant, although several are also flexible and dynamic; tend to engage migrants in solutions (often facilitate a solution); are targeted; and work in partnership, usually with actors in the country.

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

Common challenges

Language barriers between different remote communities and service providers/volunteers, as well as illiteracy, make it more difficult to effectively address migrants’ needs.

Lessons learned

Hire staff or engage volunteers (including migrants) with the cultural and language skills to interact with migrants.

Common challenges

It can be difficult to reach all persons in need without being public. Publicity can be counter-productive in countries with political opposition to such programmes.

Lessons learned

Lessons learned not identified by the study.

Common challenges

There might be a perception that the National Society helps migrants more than vulnerable locals, which might result in hostility towards the migrants.

Lessons learned

Ensure that information shared (including to the media) adheres to the Fundamental Principles, and notably avoids any perception of bias.

Involve the local community in services to truly make their delivery a space or opportunity for integration.

Common challenges

It can be difficult to find, motivate, train and retain enough volunteers to manage a programme.

Lessons learned

Contact colleges and universities and invite students to volunteer as part of their course. Disseminate information about the opportunity to volunteer to municipalities, to attract a wider and more diverse group of volunteers.

Common challenges

Services (e.g., cash cards) can act as a pull factor because they are only on one side of the country.

Lessons learned

Have a clear scale up mechanism across the country, after a small start-up programme that minimizes the pull factor.

Common challenges

Services need to be tailored to the circumstances of the migrants and their community dynamics.

Lessons learned

Engage with providers who are willing to adapt their services to cater for the migrant community and adapt services to their needs and dynamics.

Common challenges

It is often difficult to find a large pool of employers willing to employ migrants because of stigma, lack of language fluency, lack of relevant or comparable credentials, etc.

Lessons learned

Include stakeholders from potential employer companies in implementation of the programme (e.g., to provide trainings). This can encourage the participation and long-term commitment of both companies and employees.

The employer liaison role is key to creating employment opportunities. It should be filled by an individual with strong networking and persuasion skills.

Common challenges

An increased demand for support, due to a surge of migrants, can put a strain on staff, maintenance, etc. It is difficult to continuously build capacity of staff, have up to date equipment, etc.

Lessons learned

It is extremely important to have common standard operating procedures, train staff, plan for contingencies, have good coordination between different internal departments, and good collaboration with external partners.

Common challenges

It is difficult to ensure sustained funding for initiatives.

Lessons learned

It is important to diversify funding sources to ensure sustainability.

1 Challenges and lessons learned are from specific smart practices and from broader conversations with National Societies and other actors.

2 Lessons learned to address challenges may be from the smart practices that experienced the challenge or from other experiences Dalberg collected throughout the study.

Smart practices archive: Long-term