The section presents the overarching trends observed through this study across drivers of migration, needs of migrants, smart practices and enabling factors.

Key messages

Drivers of migration

People migrate in pursuit of a better life for themselves and their families. Migration can be voluntary or involuntary (due to an external shock or factor), but most of the time a combination of choices and constraints are involved. Involuntary migration is generally caused by a combination of reasons (escaping conflict and political instability, violence or disasters, because they are stateless, or have been trafficked). This report considers a migrant to be any type of vulnerable migrant, irrespective of why they migrate or their status.

Common and individual needs of migrants

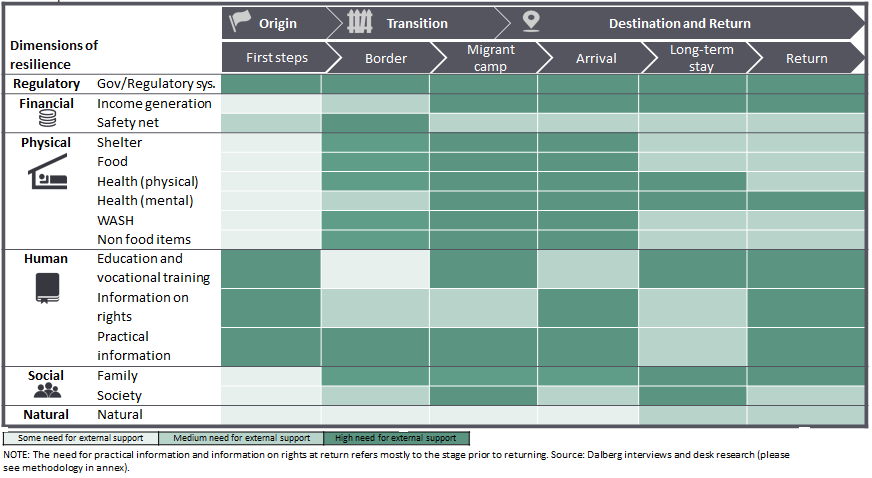

To be resilient, areas of need for external support are likely to follow a common pattern, which can be observed across the dimensions of resilience and specific needs. The pattern is, however, nuanced by each migrant’s intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics and circumstances. In migrant camps, after arrival at destination, and during transit across borders, it is more likely that migrants need support to address most dimensions of resilience. External support to address the regulatory and governance needs of migrants is essential throughout the journey; other dimensions that are likely to require support throughout the journey include restoring family links, access to regular financial sources, access to shelter, access to practical information, and psychosocial support. (Note. This report is not intended to be an exhaustive needs and vulnerabilities assessment, but uses the needs framework in the belief that needs of migrants in one context can be addressed in similar ways in other contexts.)

Smart practices

There is a tremendous need for help, and the Red Cross Red Crescent has a distinct value proposition through its unique value of volunteers, global presence, access to communities and wealth of experience. The 59 smart practices are contextualized and need to be adapted for use in different contexts. Smart practices profiled in this study include:

- Phase in the journey. Long-term stays (25), arrival (10), migrant camps (six), transition at borders (six), origin (five) and return (four). There are also three examples of smart practices that cut across multiple steps in the journey.

- Dimension of resilience. Human capital needs (~34 per cent of total) and physical needs (~29 per cent of total); fewer address social capital (~15 per cent of total), financial capital (~12 per cent of total) or regulatory and governance systems (~10 per cent of total).

- Type of support. Awareness raising (21 practices), assistance (16 practices), protection (16 practices), advocacy (six practices).

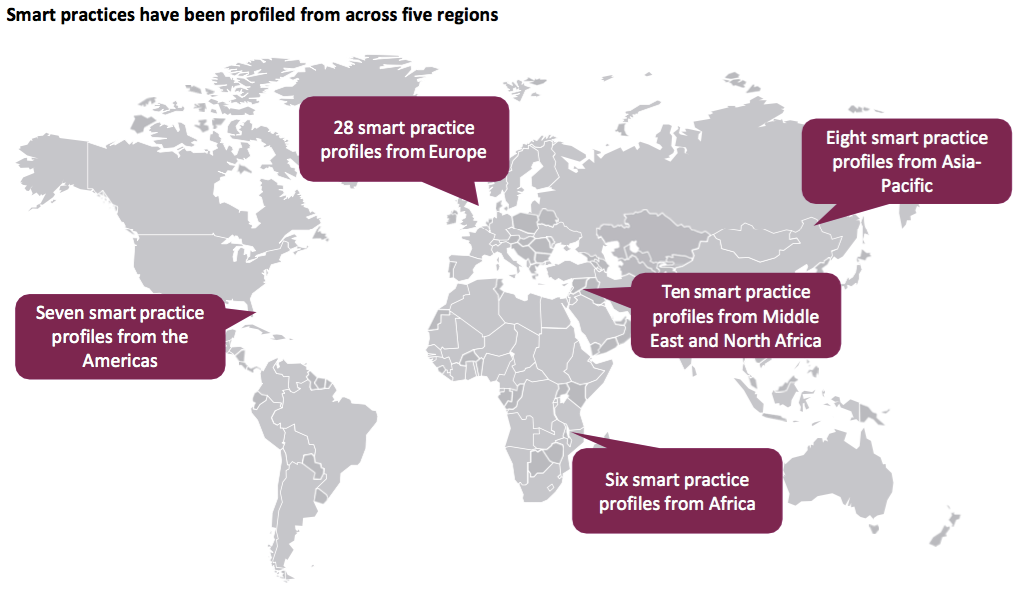

- Region: Europe (28), Middle East and North Africa (ten), Asia-Pacific (eight), Americas (seven) and sub-Saharan Africa (six).

Enablers

To be able to effectively implement a smart practice, National Societies need a set of enabling factors. These enabling factors will allow National Societies to prioritize migration, among other competing priorities. The study presents 13 examples of smart operational enablers.

Drivers of migration

This report considers a migrant to be any type of vulnerable migrant.

In order to capture the full extent of humanitarian concerns related to migration, the description of migrants is deliberately broad: migrants are persons who leave or flee their habitual residence to go to new places – usually abroad – to seek opportunities or safer and better prospects. Migration can be voluntary or involuntary, but most of the time a combination of choices and constraints is involved.

Thus, this report includes, among others, labour migrants, stateless migrants, and migrants deemed irregular by public authorities. It also concerns refugees and asylum seekers. The figure below provides a graphical illustration of some of the types of vulnerable migrant considered in this report.

1 Vulnerability is fluid and non-vulnerable migrants can become vulnerable. For example, a student could become vulnerable in the event of the outbreak of conflict.

2 Protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 protocol does not include persons fleeing from urban violence. However, protection under the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees expands the definition of a refugee to include persons who have fled their country because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.

Drivers of migration

People migrate in pursuit of a better life for themselves and their families.

People migrate in pursuit of a better life for themselves and their families. Migration can be voluntary or involuntary (due to an external shock or factor), but most of the time a combination of choices and constraints is involved.

Involuntary migration

An external shock or factor:

- conflict,political instability,violence,persecution1

- natural disaster (e.g.,drought)

- smuggled/trafficked2

- stateless person(not recognized by any government)

Results in a person losing or not having access to basic needs. For example, due to the external shock, the person might:

- not have access to the regulatory safety provided by a government

- have lost his/her livelihood and financial stability

- have lost his/her physical safety (e.g.,his/her life is at risk, s/he has lost his/her home, lack of access to food,etc.)

- have lost their family and social links.

Voluntary migration

The person decides that their current lifestyle or that of their families is inadequate, and that it cannot be improved without migrating. For example, the person might believe that:

- Their livelihood and financial stability are not sufficient.

- Their living conditions: housing, access to food and/or health are not sufficient.

- They can reunite with their families and friends in the country of destination (if these have migrated before).

- They can provide better education opportunities for their children and youth elsewhere.

- They can find better social cohesion elsewhere (for example for minorities with communities geographically dispersed).

1 Persecution as defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol.

2 Under the Palermo Protocol, trafficking is defined as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.

Drivers of migration

Four reasons are particularly common drivers of involuntary migration.

Escaping conflict, political instability, violence and/or persecution. Forced displacement due to violence, political instability or conflict is rising and presenting increasingly complex challenges to responders. There were 20.2 million refugees globally in mid-2015.1 Overall, countries immediately bordering zones of conflict, many of which are in the developing world, host the largest numbers of refugees. As of mid-2015, sub-Saharan Africa was host to the largest number of refugees (4.1 million), followed by Asia-Pacific (3.8 million), Europe (3.5 million), and the Middle East and North Africa (3.0 million). The Americas hosted 753,000 refugees.2 These numbers may have changed. For example, as of April 2016, more than 4.8 million migrants from Syria alone were in Turkey (2.7 million), Lebanon (1 million), Jordan (0.6 million), Iraq (0.2 million) and Egypt (0.1 million).4 Not all individuals fleeing violence are considered asylum seekers, and many are treated as irregular migrants without international protection.5 For example, millions of migrants are escaping gang violence in the Americas.3

Escaping disaster. Climate related disasters are also an important source of forced migration. Between 2008 and 2013, 128.4 million people were newly displaced by disasters, an average of 27.5 million people a year. 87.2 per cent of disaster-induced displacement in 2013 occurred in Asia (19.1 million people), followed by 8.2 per cent in Africa (1.8 million people), and 4.1 per cent in the Americas (892,000). The countries with the highest absolute levels of displacement in the period between 2008 and 2013 were China (over 54 million people), India (over 26 million), the Philippines (over 19 million), Pakistan (over 13 million) and Bangladesh (almost seven million).7 The UN’s figures on displaced people usually do not include migrants who leave due to natural disasters and other climate-related events. There are currently approximately 25 to 30 million environmental migrants worldwide.

Statelessness. UNHCR estimates that there are at least 10 million people worldwide who have no nationality. Statelessness may occur for a variety of reasons. In some cases, policies and laws do not recognize particular ethnic or religious groups. For example, more than one million people in Myanmar’s Rakhine state are stateless on the basis of their ethnicity, and in the Dominican Republic, tens of thousands of people of Haitian descent born in the Dominican Republic have lost their nationality. In other cases, people become stateless on the basis of gender. Some 27 states do not allow women to transfer nationality to their children, who may become stateless because their fathers are unknown, missing, or deceased. Statelessness can also occur after the emergence of new or changed states (for example, Estonia and Latvia have ~86,000 and ~262,000 stateless people respectively), or following conflict, since people may not have access to identity documents, legal employment, education and health services (although there are exceptions).8

Smuggled/trafficked. Human trafficking remains a significant source of vulnerable migrants,9 though it is difficult to know the true number of cases around the world. At present, there is no sound estimate of the number of victims of trafficking in persons worldwide. However, in 2012 the ILO estimated that 21 million people were subject to forced labour, trafficking or modern forms of slavery.10 A 2014 report by ILO estimated that forced labour in the private economy generates 150 billion US dollars in illegal profits per year. 99 billion US dollars are estimated to come from commercial sexual exploitation, while another 51 billion US dollars result from forced economic exploitation, including domestic work, agriculture and other economic activities.1

1/2. www.unhcr.org/5672c2576.html

3. www.cfr.org/transnational-crime/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle/p37286

4. http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php

5. www.npr.org/2016/02/25/467020627/why-a-single-question-decides-the-fates-of-central-american-migrants http://missingmigrants.iom.int/sites/default/files/documents/Global_Migration_Trends1.pdf

6,7. www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c15e.html

8. www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/GLOTIP_2014_full_report.pdf

9. Figures presented refer to all forced labour, trafficked and in slavery, migrants and 29 locals

10. www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_243201/lang–en/index.htm

Drivers of migration

What the drivers really mean for individual people.

Honduran migrants

Escaping violence and seeking employment opportunities.

Honduran returned migrants shared that the main reasons for leaving were insufficient employment opportunities or crime in Honduras. “When you turn 25, no one will offer you a job because you are too old,” said one person. “I have four kids, all of them graduated from college, but none of them have jobs,” shared another. “I have a job, but make just enough to live,” shared a third. Some also said they were afraid for their lives (“we leave or we are going to get killed”) or were escaping violence. A study by UNHCR in 2015 on Central American women emigrants found that 85 per cent of migrating women lived in neighbourhoods controlled by organized crime. For 64 per cent of the women interviewed, one of the main reasons for leaving was direct threats and attacks by these criminal groups. Moreover, 58 per cent of the women interviewed had suffered aggression and sexual abuse.3

Palestinian Refugees

Seeking economic opportunities.

A middle-aged Palestinian woman living in Beirut, mother of several children, explained that her husband had left Beirut to migrate to Germany last year. He travelled by sea to reach Germany. He had been a teacher at a local school, but after an accident that left his leg injured, he could no longer find a job. He also needed surgery, which he could not get in Lebanon. With the surge of migration, he had decided to migrate in search of better opportunities that would allow him to provide for his family.

Mongolian migrants

Seeking economic opportunities

A group of Mongolian women who had emigrated to Sweden over the past years (from between 12 and 2 years ago) explained that they had emigrated mostly for financial reasons: “I wished I could have somewhere I could work”. They explained that women are responsible for catering for their families and taking care of their children and so need to find sources of financial income. Moreover, additional factors enhanced their decisions to migrate. Some of these factors included human trafficking, organ harvesting, and violence against women.

Migrants from Myanmar

Estimates suggest that up to 10 per cent of Myanmar’s population migrates internationally. This includes short to mid-term migration to countries in the region mostly by irregular means. Migration to Thailand and Malaysia predominates and accounts for over three million migrants. Reasons include limited livelihoods, poor socio- economic conditions, and insecurities created by prolonged conflicts in the source communities. Better wages and demand for less skilled labour in neighbouring countries act as pull-factors.

Seeking economic opportunities

A migrant from Myanmar living in Thailand explained that she had lived with her grandmother and the grandmother’s 10 grandchildren. Her grandmother was a merchant and very poor. As the oldest granddaughter, she had to drop out of school and help her grandmother at the market. This way, her younger sister and brother were able to go to school. She had moved to Thailand hoping for better economic opportunities, despite opposition from her grandmother.

Somalian migrants

Due to insecurity, poor economic opportunities and natural calamities such as drought and flooding, about 14 per cent of the Somalian population, about one million people, have migrated, mainly to neighbouring countries. Kenya hosts the largest number, with an estimated 474,483 people.

Escaping conflict

A group of Somalian migrants in Nairobi explained that security in their home country had prompted them to leave the country. Most of them have relatives who lost their lives or who they have not been able to trace due to the conflict.

Syrian migrants

The conflict in Syria since 2011 has led to millions of people fleeing their homes. As of April 2016, more than 4.8 million migrants from Syria are in Turkey (2.7 million), Lebanon (1 million), Jordan (0.6 million), Iraq (0.2 million), and Egypt (0.1 million). Moreover, 972,012 Syrians have applied for asylum in Europe.

Escaping conflict

A Syrian young woman (in her early 20s) in Turkey had been a student of psychology, in her last year at university. She left Syria in the summer of 2015. Her family decided to leave after the mother was taken in for questioning. The mother was eventually released, but was warned that the whole family would be under continuous supervision. They left with what little they could bring to the neighbouring country, Turkey, seeking safety. She was a volunteer at the Syrian Arab Red Crescent before her family migrated. She is now a volunteer with the Turkish Red Crescent Society.

Congolese migrants

At least 70 armed groups are believed to be currently operating in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).3 As a result of the conflict, some 430,000 migrants from the DRC are in neighbouring countries, particularly Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania.

Escaping violence

A young Congolese man of 19 in Nairobi explained that his father was one of the educated people in the village. The militias tried to find and kill him. As a result, his father fled and the son has have never seen him since, although he received news that his father had died in Kenya. After the father fled, the family tried to force his mother to marry another member of the family, in accordance with tradition. His mother refused and started to be attacked by the family. Once she had saved some money, she fled with her four children.

Common needs

To be resilient, areas of need for external support generally follow a common pattern.

The IFRC believes that the best way to support migrants is by helping them be resilient throughout their journey. By being resilient, migrants will be able to better bear the risks and overcome the external shocks associated with migrating. While all dimensions of resilience are important, certain dimensions are more pronounced at some moments in the journey than at others.

- First steps. At origin, migrants need access to information, training and support to ensure that regulatory systems protect their rights.

- Transition through borders. As they continue the journey, regulatory safety and access to practical information remain important, and having a financial safety net, maintaining family links, and addressing physical needs (access to shelter, food, health and general safety) become more pressing.

- Migrant camp. If their journey is held up at a migrant camp, the regulatory system will determine a migrant’s access to basic needs, such as employment. Employment opportunities can enable migrants to cater for several of their needs. If not, it is likely that they will require external support for all physical needs, education, practical information and psychosocial support. Social needs start to become more important, as they need to be accepted by the host community, integrate with the camp community, and may have more time to restore family links.

- Arrival. Migrants need to be able to access a fair and personalized regularization process and access basic needs when they arrive at their destination. While waiting for the decision, they will need access to financial income, or other means to provide for all basic needs. Information on the process, their rights and practical information on how to access temporary housing, food, health care, education, legal assistance, psychosocial support, etc., are vital. They can seek to re-establish broken links with their families. Acceptance by potential host communities can help overcome the remaining challenges, and help with future integration.

- Long-term stay. Migrants need to be able to remain in the country, leave it safely when desired, and access housing, food, healthcare, education, and employment opportunities. Particularly important is access to income generating opportunities, which will allow them to become self-sufficient. However, even when a migrant has a job or access to financial income, salaries are often lower, and hence housing, food, etc. are precarious and external support may be needed. As physical needs are covered, the need for psychosocial support increases in importance as migrants become ready to start overcoming the traumas they escaped or experienced during their journeys. Children, youth and some adults need access to education and vocational training. They can seek to fully re-establish broken links with family. They also need to feel part of the new community; however, language and diverse cultural norms may be barriers to integration.

- Return.1 No individual may be returned to a country in violation of the principle of non-refoulement. In many cases, when migrants return to their country of origin, they are in a more vulnerable financial state than when they left. Income generating opportunities need to be available. Psychosocial support is often extremely important to overcome traumas and a feeling of failure. Reunification with family in the country of origin is also important, as family members often help returned migrants by providing shelter, food, etc.

1 Return in this report refers to return to country of origin. It does not consider moving to a third country as the needs for this type of movement are covered at different stages (i.e., transition through borders, migrant camp, arrival, and/or long term stay). Dalberg interviews and desk research.

To be resilient, migrants need to have six dimensions of resilience (regulatory, financial, physical, human, social and natural), and may need support to realize them. Each dimension of resilience is composed of specific needs. The table below provides an overview of the common needs for external support that migrants may have across the journey. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support. The shading of the need for support is relative to both other needs in the same step in the trail, and to the same need at other steps in the trail.

Some steps in the trail and some dimensions of resilience tend to require more external support.

External Support at Each Stage of the Journey

- In migrant camps, on arrival at destination, and during transit across borders, migrants are likely to need support to address most dimensions of resilience. This is likely because at these stages migrants are more exposed to potential external shocks or more dependent on external actors to provide for their needs (for example in migrant camps). Moreover, at these stages they tend to have fewer opportunities to rely on their own capabilities to cater for their dimensions of resilience. For example, at these moments it is more difficult to find sources of income, or to rely on families and friends.

- During long-term stays and return, it is likely that migrants need support to address several dimensions of resilience. This is likely because at these stages migrants tend to have more opportunities to rely on their own capabilities to cater for their dimensions of resilience. For example, they might find sources of income, or be able to rely on families and friends. However, it is still highly likely that a large proportion of migrants are not able to cater for their dimensions of resilience and require support across most dimensions.

- In the country of origin, most needs are not yet applicable because the migrant may not yet be in need or because needs are addressed by initiatives that target IDPs or vulnerable nationals (not the focus of this study). The only need of future international migrants that can be addressed through initiatives that are not targeted at IDPs or vulnerable nationals is the provision of relevant information to prepare them for their international journey, and advocacy to ensure migrants can leave the country safely.

External Support for Each Dimension of Resilience

- External support to address the regulatory and governance needs of migrants is essential throughout the journey. This is likely because the migrant is too distant from decision makers to advocate directly. Yet the migrant’s regulatory status throughout the journey will heavily influence his/her vulnerability and need for external support in other areas. For example, if a person is not allowed to legally cross a country s/he will need to take more dangerous routes. If a person is not allowed to work during transit or at destination, s/he will not be able to provide for him or herself. If s/he is not allowed to legally rent accommodation, s/he will sleep on the streets, rely on the black market, or have to rely on external support.

- Other areas that are likely to require support throughout the journey include restoring family links, access to regular financial sources, access to shelter, access to practical information, information on rights and psychosocial support.

- The other needs also require external support throughout most steps of the journey, but the need is more urgent at specific steps in the journey. Nevertheless, a large proportion of migrants are likely to need support to address such needs throughout the trail.

- Natural capital, while important, requires less external support during the migration journey. Responses in countries of origin, and during transit and at destination, that address natural capital are normally addressed by development initiatives in the country, and are not completed with a migration perspective.

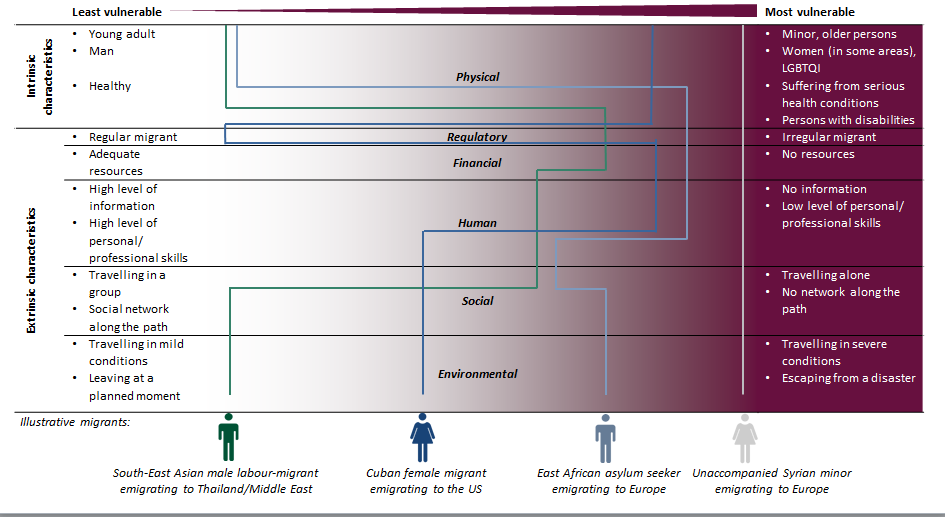

Individual needs

The pattern is nuanced by each migrant’s intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics and circumstances.

The IFRC believes that the best way to support migrants is by helping them be resilient throughout their journey. By being resilient, migrants will be able to better bear the risks and overcome the external shocks associated with migrating. While all dimensions of resilience are important, certain dimensions are more pronounced at some moments in the journey than at others.

The response of National Societies

There is a tremendous need for help; the Red Cross Red Crescent has a distinct value proposition.

Unique value of volunteers.

The Movement currently has more than 17 million active volunteers.

Global presence.

It is the only organization with a presence in 190 countries.

Access to communities

Through its volunteers in local branches, the Red Cross Red Crescent has access to communities, including in the hardest to reach areas.

A wealth of experience.

Together, National Societies can boast of multiple smart practices in addressing the needs of migrants, as well as years of experience in the sector.1

1. This report is focused on helping the Red Cross Red Crescent consolidate its wealth of experience in a specific area.

The response of National Societies

National Societies and partners offer a wealth of smart practices.

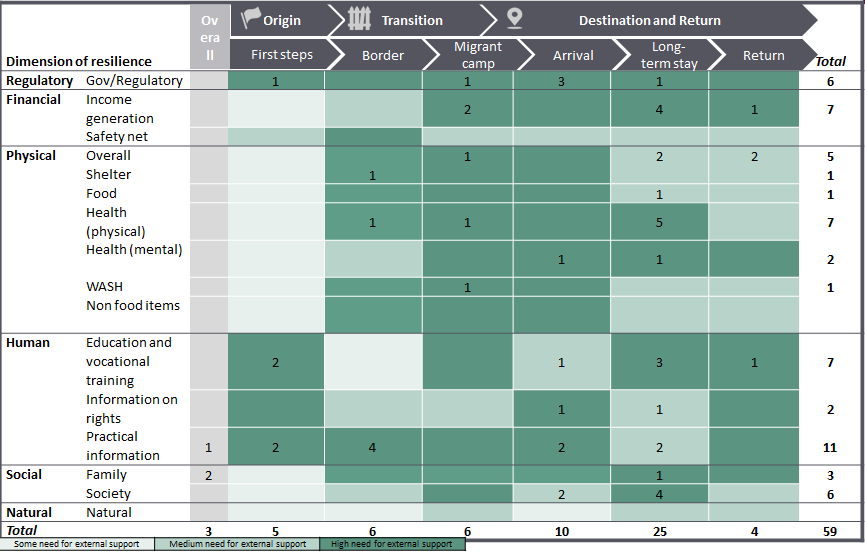

NOTE: Numbers indicate the number of smart practices identified in this report at each step that correspond to each dimension of resilience as the primary dimension filled. Though several smart practices cut across dimensions of resilience, we only counted the primary dimension filled by the smart practice for the purposes of this analysis.

The study identified smart practices from every region, during each phase of a migrant’s journey, and for every dimension of resilience. The 59 smart practices profiled in this study represent a wealth of ideas that can inspire National Societies and other actors to develop new approaches for meeting migrant needs.

- Phase in the journey. Most interventions found in the study occur during long-term stays (25), followed by at arrival (10), in migrant camps (six), and during transition across borders (six). There are fewer examples of support in countries of origin (five) and at return (four). There are also three examples of smart practices that cut across multiple steps in the journey.

- Dimension of resilience. The study includes a large number of practices that support human capital needs (~34 per cent of total) and physical needs (~29 per cent of total), Fewer address social capital (~15 per cent of total), financial capital (~12 per cent of total) or regulatory and governance systems (~10 per cent of total). When considering specific needs within dimensions of resilience, many examples of practices address practical information, education and vocational training, income generation, and physical health; fewer provide shelter, food, non-food items, safety nets, or water, sanitation and hygiene.

- Type of support. Most smart practices identified focused on awareness-raising (21 practices), followed by assistance (16 practices) and protection (16 practices). Fewer focused on advocacy (six practices).

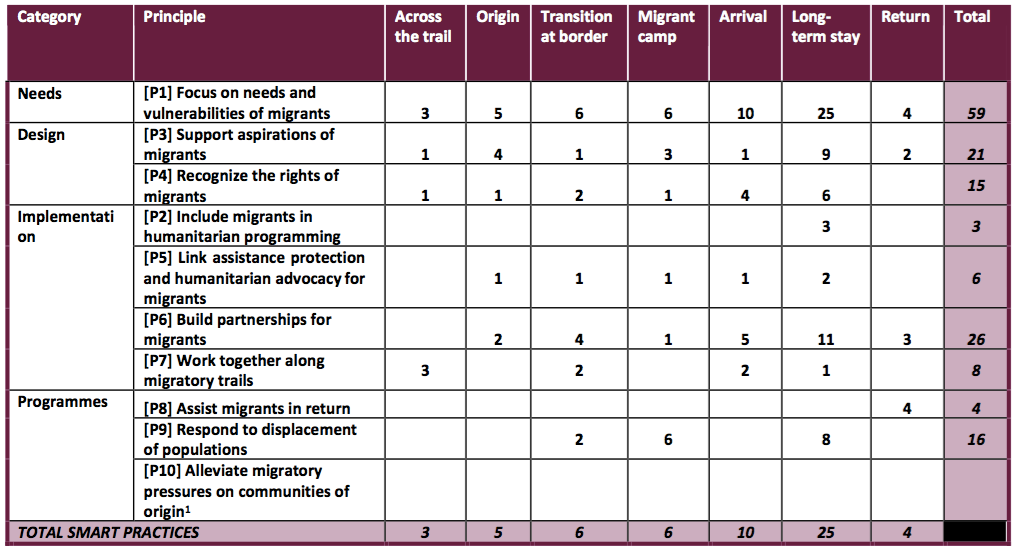

Together, the smart practices address most of the IFRC migration principles.

Though smart practices covered a range of principles, fewer seem to include migrants in humanitarian programming (P2), link assistance, protection and advocacy [P5], or work along the migratory trail [P7]. Four practices assist migrants in return [P8]; none alleviate pressures on communities of origin.1

1. Responses that seek to alleviate migratory pressures on communities of origin were not included as part of the scope, as these should fall under initiatives that work with 40 vulnerable populations through domestic responses.

The smart practices identified in this report come from all regions of the world.

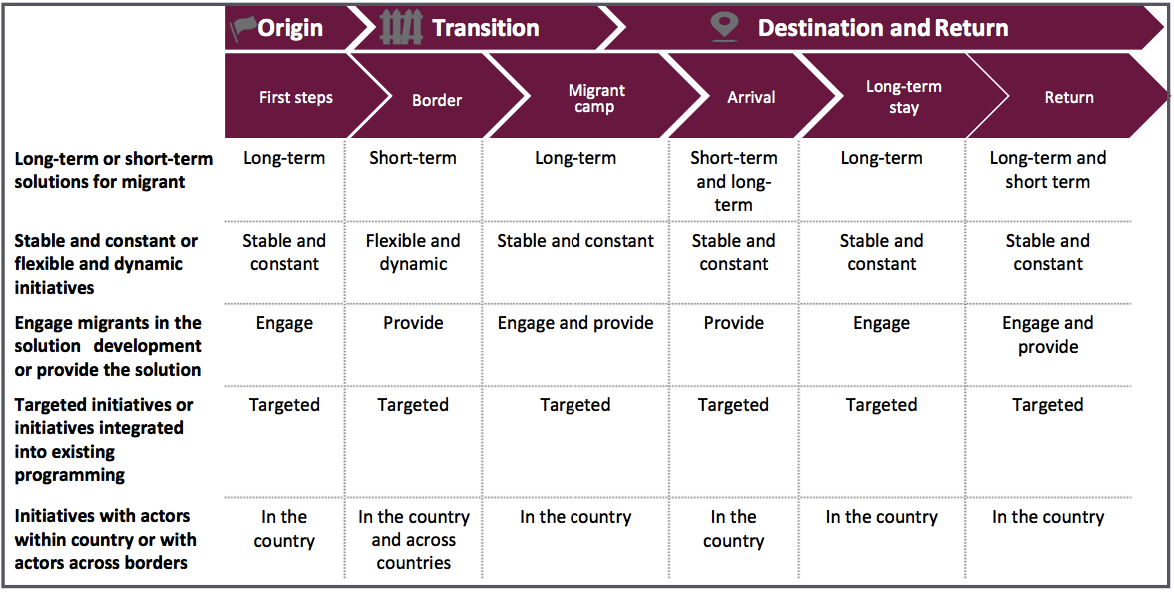

Five primary design choices in the development of smart practices were identified.

Smart practices were compared across five simple criteria, to analyse the following:1

- Long-term or short-term solutions for migrants

- Refers to whether the response targets mostly immediate needs, or seeks to ensure that migrants’ needs are covered over the long- term (including for the migrant to provide for their own needs).

- The focus on providing long-term or short-term solutions varies by step. At faster and shorter-term moments (transition across borders), responses tend to address short-term needs, to respond to the nature of migration at that stage. At the other stages, which are less “fast”, responses tend to focus on providing long-term solutions. Because short-term needs exist at all stages, there are also responses throughout that focus on providing short-term needs.

- Stable and constant or flexible and dynamic initiatives

- Refers to whether the target beneficiary, service provided, or period, or location of provision, is subject to change or remains constant and predictable.

- The nature of the step tends to indicate the dynamics of the support. At faster and shorter-term moments (transition across borders), responses tend to be flexible and dynamic, to respond to the nature of migration at that stage. At the other stages, which are less “fast”, responses tend to be more stable and constant. However, responses at fast and short term moments should be planned and structured in advanced, while responses at “less fast” moments should be flexible enough to adapt to needs. Moreover, there is probably a need for more flexible and dynamic responses at arrival and return (particularly for the return journey)

- Provide the solution or engage migrants in finding the solution

- Refers to whether initiatives directly provide a solution for the migrant, or empower the migrant to be part of the solution, for example by providing tools and skills, or choices.

- The nature of the step tends to indicate the nature of the support. For example, shorter-term moments (transition across borders, in migrant camps, arrival, and return), responses tend to provide solutions, while at longer-term moments (origin, migrant camps, long- term stays, and return) they tend to engage migrants in the response. While the urgency of shorter-term moments explains the need to provide responses, there is probably an opportunity to further seek ways to engage migrants in the response at these stages as well.

- Targeted initiatives or initiatives integrated into existing programming

- Refers to whether initiatives are developed and tailored mostly for migrants, or incorporate migrants in broader responses.

- Most of the smart practices identified for this report are targeted. This is likely to be because actors who provided inputs prioritized sharing targeted initiatives. It is likely that more integrated initiatives exist in countries of origin, during long-term stays and at return. If not, we recommend further mainstreaming a migration lens across existing initiatives. At transition across borders, in migrant camps and on arrival, migrants generally need more targeted solutions, given the nature of these stages.

- Initiatives with actors within country or with actors across borders

- Refers to whether initiatives work mostly with actors within national borders (i.e., local actors and international actors with operations in the country) or mostly with actors in other countries.

- With a few exceptions, most of the smart practices identified for this report work with partners within the country. While this might be expected in migrant camps and during longer term stays, there is a large potential for more cross-border initiatives. This would be particularly relevant at origin, transition, arrival and return.

1. Common characteristics are not intended to assess what smart practices should be, but are descriptive of what has been found. They are meant to highlight that there generally are commonalities and provide an idea of some important considerations for developing smart practices.

A few common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

To reach migrants or migrant communities and make them aware of the services available.

Creating strong links with communities or migrant groups, many of whose members are departing or transiting or incoming migrants, can make it easier to support them.

To identify unmet needs and to monitor and evaluate whether the support provided has addressed them. This is particularly challenging when migrants quickly move away to another place after receiving a service and if the benefits of a service are only apparent to the migrant at the next step in the journey.

Creating links with subgroups of migrants and encouraging them to supply feedback along the trail can help to obtain feedback.

Gathering feedback from migrants at one step in the trail regarding support received at an earlier stage, could be an approach for cross- border collaboration and a way to improve services to migrants.

To provide support to irregular migrants in complex political situations.

Appealing to the Red Cross Red Crescent humanitarian mandate has been a successful approach used by some National Societies.

Working discreetly, without generating too much publicity, has in some situations led the government to “turn a blind eye” to support given.

Creating a clear value to the government, by, for example, providing anonymized data on the number of irregular migrants in specific areas, can result in the government accepting that support is provided.

To provide all the services migrants need at a given step through one organization.

Working in close collaboration with partners, even at one location, is an effective way to leverage the skills of each partner and ensure high quality services to the migrants.

To avoid generating a perception among vulnerable host populations that the National Society helps migrants more than host populations. This can result in hostility towards migrants.

Including the most vulnerable host populations in the response, by using clear vulnerability criteria that include both migrants and the host population, can reduce tensions.

To address sensitive issues such as sexual violence or abuse with migrants.

Working regularly with migrants and their community leaders, and gaining their trust, should be a first step before addressing sensitive issues.

Involving migrants directly in efforts to address sensitive issues with their peers can be a less threatening way to encourage migrants to discuss sensitive issues.

To attract, develop and retain talent among staff and volunteers.

Recruiting volunteers through a wide dissemination strategy that communicates with migrants, students, and the host community can be a away to attract new talent. Generating agreements with colleges, universities, or the private sector, whereby volunteering becomes part of the curriculum requirements or side activities, can further enhance interest and result in a more diverse group of volunteers.

An increased demand for support, due to a surge of migrants, can put a strain on staff, maintenance, etc. It is difficult to continuously build capacity of staff, have up to date equipment, etc.

It is extremely important to have common standard operating procedures, train staff, plan for contingencies, have good coordination between different internal departments, and good collaboration with external partners.

Some National Societies are cautious of engaging in open advocacy, due to the risk of being perceived as being in open conflict with the government.

Minimal support from the IFRC or a sister National Society can sometimes help a National Society find constructive ways to advocate.

Despite strong political stances, some governments are appreciative of an evidence-based approach to advocacy and see it as a way to keep the government updated on the real situation.

A collaborative approach with the sector and key government departments is key to change.

The power of the Red Cross Red Crescent brand can be harnessed to advocate for change.

Using clear evidence of the humanitarian problem together with a focused solution is an effective strategy.

Evidence collection and advocacy should be embedded in programming and staffing at all levels.

Services need to be tailored to the circumstances of migrants’ situations and their community dynamics.

Engage with providers who are willing to adapt their services to cater for the migrant community and adapt services to their needs and dynamics.

It is difficult to ensure sustained funding for initiatives.

Lesson learned not identified during the study.

In some contexts it is difficult to provide holistic information to migrants due to risk of being seen as encouraging or deterring migration. it requires judgement to know what types of information can and cannot be provided. Decisions can affect migrants’ trust in the service provider.

Lesson learned not identified during the study.

To effectively implement smart practices, a set of enabling factors need to be in place

To be able to effectively implement a smart practice, National Societies need a set of enabling factors. These enabling factors will allow National Societies to prioritize migration, among other competing priorities.

First, the enabling factors will allow a National Society to know that there is an unmet need, and second, to be able to address it. These enabling factors are: (i) human capital, (ii) technical capital, and (iii) financial capital, as well as iv) favourable political, and v) social/cultural contexts.

Several National Societies and partners have developed smart operational enablers (tools, systems, processes, etc.) to strengthen their capacities. The study presents 13 examples of smart operational enablers:

- Four smart operational enablers improve the technical capacity to know where there is a need.

- Four smart operational enablers develop human capacity to address need.

- Seven smart operational enablers strengthen technical capacity to address needs.

- One smart operational enabler increases financial resources to address needs.

Moreover, the IFRC can further support National Societies to conduct national or regional needs assessments by providing technical or financial support. The IFRC can also further support National Societies to ensure that enablers to address migrants’ needs are present. Some examples include: adapting existing tools and guidelines so that they are relevant to migration; developing a migration trust fund; or leading with a strong unified global voice on migration at global level. These are further detailed in the Chapter “Enablers of Success”.