Responses to migrants’ needs in migrant camps

The journeys of some migrants will include a stay in a migrant camp. Taking into consideration various characteristics, this section considers migrants who stay in a camp with the intention of being re-settled to a different country, migrants who stay in a camp until they can return to their country of origin, and migrants who stay in a camp until they settle in the country that hosts the camp. The following section presents an overview of the needs of migrants in migrant camps and six smart practices that address some of those needs.

Key messages of this section

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

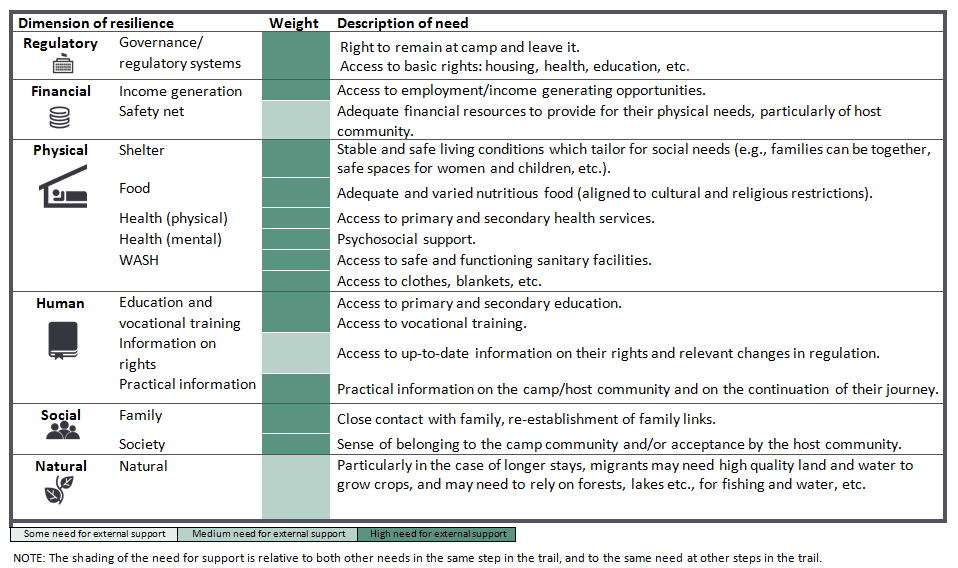

- The needs in migrant camps cut across all dimensions of resilience. As a migrant arrives to and integrates in the camp, his/her needs will evolve from mostly physical capital, towards a heavier focus on regulatory, financial, social, human and natural capital. This is mostly because the stay at a migrant camp can vary significantly, from a few weeks to decades.

SMART PRACTICES

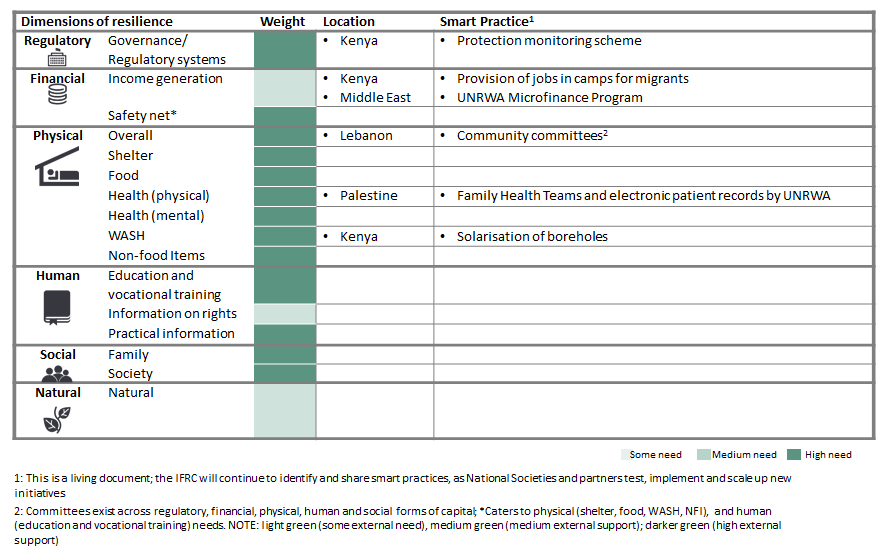

- Most of the smart practices identified target physical needs.

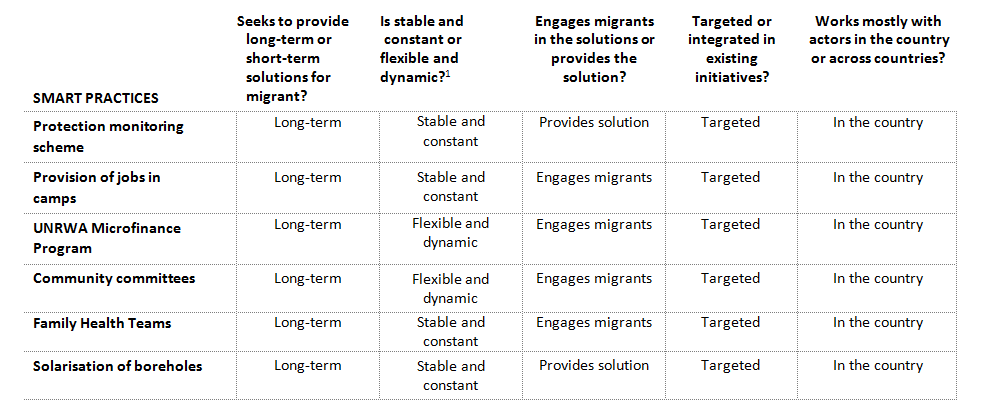

- The smart practices identified have several characteristics in common. Most seek to provide long-term solutions for migrants, with the vision that migrants may remain for several years; are constant and reliable, providing migrants with stable support while being flexible enough to identify and address their changing needs; engage migrants in solutions, though sometimes directly provide solutions; are targeted initiatives; and work in partnership with actors in the country.

- When addressing the needs of migrants in migrant camps, actors have faced some common challenges. These include: unequal distribution of support across camps, language barriers, cultural barriers in some areas, and tensions with neighbouring vulnerable communities. Some lessons learned are: to create a clear map with roles and responsibilities, to include the most vulnerable host populations in the response, to engage regularly with community leaders, and to engage migrants with language skills in the response.

The needs in migrant camps cut across all dimensions of resilience

This section considers the needs of migrants in migrant camps. Stays in migrant camps have different natures and include: migrants who stay in a camp with the intention to be re-settled to a different country; migrants who stay in a camp until they can return to their country of origin; and migrants who stay in a camp until they settle in the country that hosts the camp. As a result, migrants may remain for a few weeks, or for decades. It is estimated that the average duration of major refugee situations (protracted or not) has increased from nine years in 1993 to 17 years in 2003.1

1 www.unhcr.org/40c982172.pdf.

As a migrant arrives and integrates in the camp, his/her needs will evolve:

Governance/regulatory systems. Throughout his or her stay, a migrant needs to be able to remain at the camp for as long as needed or agreed. Similarly, s/he needs to be able to leave it safely when needed. During the stay, the migrant also needs to have access to basic needs such as housing, food, healthcare, education and employment opportunities.

Financial capital. Particularly important for longer stays at camps is access to employment or income generating opportunities. S/he might find these opportunities in the camp or in a neighbouring community. With a few exceptions, however, there are often legal restrictions on migrants that impede them from legally working outside their camps. Lack of economic opportunities is likely to have negative impacts on their physical, mental and social capital.

Physical capital. Initially when migrants arrive in a camp, their physical needs are most urgent. They need access to adequate shelter that is tailored to environmental conditions (cold, rain, heat, etc.) and their social needs (safe and private spaces for them, their children, and the rest of the family). When they first arrive at the camp, they will often also need medical assistance and highly nutritious foods, as they may be malnourished, exhausted and unwell from the journey. As they stay longer, needs evolve into, for example a desire for diverse foods and dishes. An interviewee confirmed that migrants often seek to re-establish their ordinary lives as much as possible: “WFP is giving a standard ration of maize, beans, cooking oil, salt – however if you go round the camp you will see they have graduated from this. People are eating pasta, rice, milk – things that are not in the basic ration.”

As migrants stay longer, the need for psychosocial support also increases in importance, as they will be ready to start overcoming the traumas escaped or experienced during the journey. Because of the longer stay, they may also have developed a stronger trust relationship with the psychosocial assistant, facilitating psychosocial support.

Human capital. Children and youth need access to primary education, secondary education and vocational training. Otherwise they risk losing months or years of schooling, which in the long-term can make them less resilient. Overall, the migrant will also need access to up-to-date information on his or her rights and relevant changes in regulation, as well as practical information on the camp and on the potential continuation of his or her journey. The need for information can become particularly important, as camps may be located far from other sources of information.

Social capital. The social needs of migrants increase in importance the longer they stay at the camp. Migrants will often seek to re-establish broken links with their families, if possible. In some cases, they go to specific camps or regions seeking to reunite with their families there. Because of the potential longer-term stay at the camp, migrants need to feel part of the community. This can be the camp community or the local hosting community. “Refugees in the camps need to feel like they are contributing to society,” explained an interviewee. It is worth noting that, in some cases, migrants are not allowed to leave their camps, meaning integration with the local community is more difficult to achieve.

Natural capital. Lack of natural capital (poor quality of atmosphere, biodiversity, water, land and forest) may be a driver of migration and should have been addressed as part of initiatives for vulnerable populations. The need for natural capital becomes more important again at a migrant camp, particularly if migrants stay for a long period. This is because they may need high quality land and water to grow crops, or may rely on forests or on lakes for fishing and water, etc. (It is worth noting, however, that for this report no initiatives were found that address natural capital in the host community, with the migrant in mind).

The table below provides a high-level summary of the common needs for external support that migrants may have. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for physical and financial capital

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, LEBANON

Financial capital was seen as a key need to cover most of the physical capital needs. Syrian migrants who had been living in a camp in Lebanon for the past few years explained that financial resources were a key need. They relied on financial support from UNHCR (130 US dollars per month per family) and sporadic agricultural work, which paid 5 US dollars per day, when they could find it. Yet financial needs were high, as they had to rent the land on which they had their tents from a local land owner (70 US dollars per month), pay for electricity and water, pay for health care, and sustain large families.

Dire shelter conditions expose migrants to dangerous situations. The shelter conditions of Syrian migrants at two makeshift encampments in Lebanon were inadequate during parts of the year. Made of tarpaulin, inside the tents temperatures could be as high as +48C in summer and as low as -9 C in winter. Moreover, fires due to poor electric cabling were common. In one camp, there had been an average of three fires per month before cabling was improved. Floods were also common (before the construction of evacuation canals) and could lead to the spillover of latrines, soaking of mattresses and blankets, and spreading of diseases.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Limited financial opportunities within migrant camps lead to migrants leaving the camps in search of employment opportunities outside. Congolese urban migrants shared that they knew that the camps provided services. However, because they felt they could not further improve their situation in the camps, they decided to leave for Nairobi and choose a life of irregular status which nevertheless might allow them to find employment.

Examples of the need for human and social capital

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, LEBANON

Busy roads to the nearest schools result in lack of education for some migrant children: Syrian migrants at two makeshift encampments in Lebanon were not able to send their children to school. While education was available, the closest school was some distance away from the camp, and parents were worried about safety conditions for children to cross the busy roads alone.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Enmity among migrants in camps forces some to flee in search of safety. Several Congolese migrants also explained that they had left their camps, seeking security away from other migrants in the camp. A Congolese urban migrant said that, for his safety, he could not stay at a migrant camp. For tribal reasons, their family was targeted for elimination. They were on holiday from school when rebels came to attack and kill the family. After torturing his family, they killed them. He was shot as well but managed to escape through a window and fled. He found a timber truck that was travelling and hid in it, and when he came out he was in Nairobi. In Nairobi he met someone who took him to the church and gave him a bit of money and directions to UNHCR, where he registered and went into a camp. Unfortunately, his attackers sent people to find and kill him. At the camp, he was attacked once by people who told him: “Do you think you can escape that easily?” He fled the camp and went to the city.

Most smart practices identified target physical needs

Smart practices identified at this stage are provided in the table below.

Common characteristics of smart practices

The smart practices identified at migrant camps have several common characteristics. Most seek to provide long-term solutions for migrants, with the vision that migrants may remain for several years; are constant and reliable, providing migrants with stable support but flexible enough to identify and address their changing needs; engage migrants in solutions but sometimes directly provide solutions; are targeted; and work in partnership with actors in the country.

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

Common challenges

Some camps (particularly self-established migrant camps) may receive less support than others.

Lessons learned

Create a clear map with all camps and distribute roles and responsibilities among key actors supporting camps.

Common challenges

There is a possibility that tensions may rise with neighbouring poor local populations who might feel entitled to similar programmes.

Lessons learned

Include the most vulnerable host populations in the response, using clear vulnerability criteria that include both migrants and the host population.

Common challenges

It can be initially difficult for migrants to address sensitive issues such as sexual violence within communities.

Lessons learned

Regular engagement with migrant leadership groups is important to build trust with the community and flag sensitive issues in the community which may otherwise be missed.

Common challenges

Language barriers between different communities and service providers/volunteers make it more difficult to effectively address migrants’ needs.

Lessons learned

Engage migrants with language skills as volunteers (or paid translators).

Smart practices archive: Camp