Responses to migrants’ needs during the first steps in a country of origin

This stage includes preparatory steps to migrate internationally. For this report, this step does not consider IDPs. The following section presents an overview of migrants’ needs in the country of origin as well as five smart practices that address some of these needs.

Key messages of this section

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

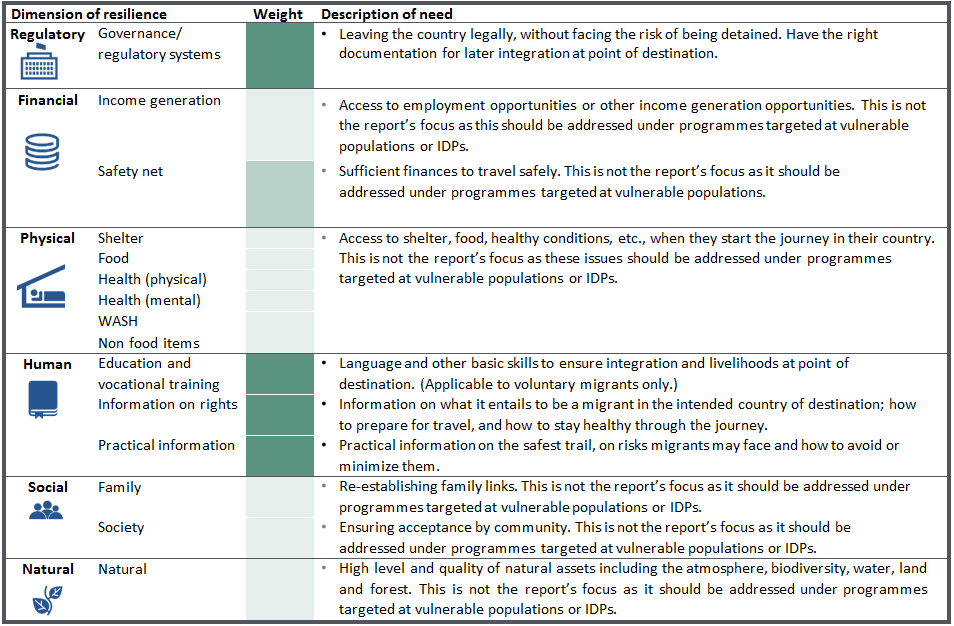

- When a person has made the decision to migrate, the main needs for external support are for regulatory safety and access to reliable information. While other needs are also important, either these have been drivers of migration and should have been addressed through initiatives that target vulnerable populations in the community; or they are needs that are addressed through responses that target IDPs. These other needs and their responses have hence not been considered for this report for this stage.

SMART PRACTICES

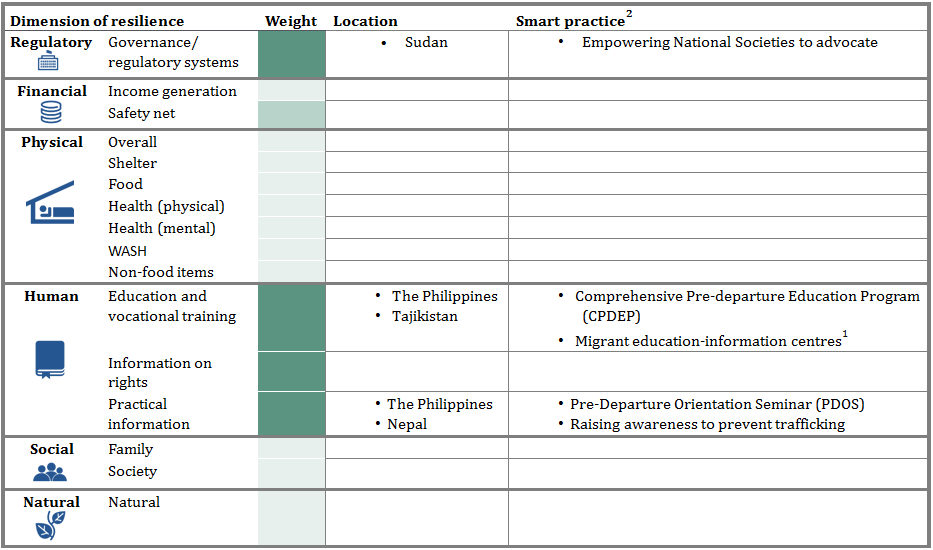

- The smart practices identified target regulatory and governance needs, as well as human capital needs of voluntary migrants. The study was not able to identify initiatives in countries of origin that provided relevant information to involuntary migrants.

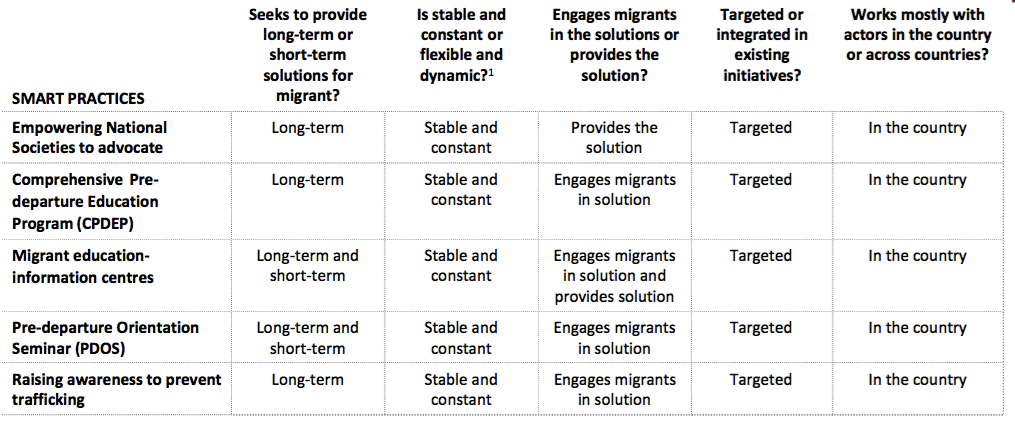

- The smart practices identified have a few characteristics in common. These are: working on long-term solutions, engaging migrants in the solutions, targeted initiatives that focus on one type of support; and working in partnership, mostly with local actors.

- When addressing the needs of migrants in countries of origin, actors have faced a few common challenges. These include: to identify and support migrants when they are leaving the country of origin; to ensure migrants are aware of support when support is available; to assess whether migrants acquire necessary and relevant information from the support; to decide on which partners to work with; and whether or not to engage in advocacy. Some lessons learned are that: strong links to communities with a high level of departing migrants increase the potential to support them; it is key to closely monitor the quality of training and information that are provided to outgoing migrants; the inclusion of civil society inputs is important; and that minimal support from the IFRC or a sister National Society can be enough to spur a National Society to engage in successful advocacy on migration.

When a person decides to migrate, the main needs are regulatory safety and information

When a person has made the decision to migrate, the main needs for external support are regulatory safety and access to reliable information. While other needs are also important, either these have been drivers of migration (for example, lack of adequate financial income, lack of social capital, lack of physical capital, or lack of natural capital) and should have been addressed through initiatives that target vulnerable populations in the community; or they are needs that are addressed through responses that target IDPs (for example provision of shelter, food etc. after a natural disaster or conflict). These other needs and their responses have hence not been considered for this report.

Governance/regulatory system. While lack of regulatory safety can be a driver of migration (e.g., for stateless populations), migrants also need to have the regulatory safety to leave the country legally, without facing the risk of being detained. They also need adequate documentation for later integration at their destination.

Financial capital. Lack of financial capital is a common driver of migration, and should have been addressed as part of initiatives with vulnerable populations. When migrants have made the decision to migrate, they need money to cater for as many of their needs as possible. In many cases they will rely on savings or loans from family members and others. Initiatives to increase those savings (e.g., through income-generating opportunities) before they leave would be considered as initiatives for vulnerable populations, and are therefore not the focus of the report.

Physical capital. Lack of physical capital (e.g., due to a natural disaster or conflict) is a common driver of migration, and should have been addressed as part of initiatives for vulnerable populations. When migrants have made the decision to migrate, they might need physical support while travelling within the country. However, at this stage they are not yet migrants and should be catered for as IDPs. Initiatives to support physical capital at this stage, are therefore not the focus of the report.

Human capital. Lack of human capital (education and skills) is often a driver of lack of financial capital, which in turn is a driver of migration. Here, access to adequate skills and information specifically for the migration journey may require external support at this stage.

- Specific skills for the journey may include foreign language skills or basic skills for the work migrants might perform on arrival (e.g., computer literacy skills). The possibility to access training once a person has decided to migrate is, however, only a need that voluntary migrants can have the time to address.

- Specific information required includes practical information on possible destinations, trails and ways to remain safe during the journey. It also includes information on the rights they have (and do not have) while travelling and at destination. Access to reliable information may result in decisions not to migrate, to migrate along a different trail, to migrate by different means, to migrate to a different country, etc.

Social capital. Lack of social capital (e.g., loss of family members due to a natural disaster or conflict, or non-acceptance of the person by the community) can be a driver of migration. Where possible these should have been addressed as part of initiatives for vulnerable populations; or can be addressed as part of initiatives for IDPs (e.g., tracing of missing people as a result of natural disaster or conflict). If lack of social capital is not a driver, migrants will need to stay in touch with their family members, but this is not yet a need at this stage. Initiatives that address social capital at this stage are therefore not the focus of the report.

Natural capital. Lack of natural capital (poor quality of atmosphere, biodiversity, water, land and forest) can be a driver of migration, and should have been addressed as part of initiatives for vulnerable populations. However, need for natural capital will no longer be essential once the person decides to and starts to migrate. Initiatives that address natural capital at this stage are therefore not the focus of this report.

The table below provides a high-level summary of the key needs of migrants as they start their international journey. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for human capital (information)

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Where possible, migrants access information from friends and relatives with relevant experience. Honduran returned migrants explained that they had had some information about their rights, but not all the information they needed. They explained that they knew they were breaking the law and had an idea that if they got caught they would, for example, be thrown in jail in the US for 3-7 months and then be deported. “We all know about the risks of the trail, but we think they might not happen to us, or we are willing to take them. We also know that out of 10 only one makes it.” This information was mostly gathered by word of mouth, from those who had already migrated (and returned).

MONGOLIAN MIGRANTS, SWEDEN

In some cases, migrants rely on traffickers to take them somewhere. Several Mongolian migrants in Sweden explained that they did not know where they were going: they had paid the trafficker and ended up in Sweden.

In other cases, migrants rely on internet as a source of information. Others, who had specifically chosen Sweden, explained that they had found on the internet that Sweden was a good place to go to.

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, LEBANON

Where possible, migrants access information from friends and relatives with relevant experience. A community of Syrian migrants living at a camp in Lebanon explained that, when they decided to leave, Lebanon was the clear option. They had all been part of the same community in Syria, and some of their elders had lived in Lebanon before. Moreover, a man from their village had lived in Lebanon for over 20 years and had been able to secure land for them to rent and install tents on. Through their contacts they had known what to expect upon arrival.

ETHIOPIAN MIGRANTS, KENYA

Incomplete knowledge of their rights at destination creates a false perception on what migrants can expect in the country of destination. Ethiopian migrants in Kenya shared that they went to Nairobi, Kenya, thinking it was a safe haven. However, once they arrived, they realized that they could be deported back to Ethiopia.

Most smart practices identified target human capital needs (information and skills)

The interventions identified in countries of origin address the needs of voluntary migrants. Some examples are provided in the table below. We were not able to identify initiatives in countries of origin that provided relevant information to involuntary migrants.

1. Migrant education-information centres also provide practical information to migrants. NOTE: light green (some external need), medium green (medium external support); darker green (high external support).

2. This is a living document; the IFRC will continue to identify and share smart practices, as National Societies and partners test, implement and scale up new initiatives.

Common characteristics of smart practices

The interventions identified in countries of origin address the needs of voluntary migrants. Some examples are provided in the table below, and are further detailed in the pages that follow. We were not able to identify initiatives in countries of origin that provided relevant information to involuntary migrants.

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

Common challenges

To identify and support migrants when they leave the country of origin. When migrants decide to migrate, it is seldom that they publicize it or report it to anyone. The Red Cross Red Crescent often only interacts with migrants at the border or in the new country. By then, migrants will already have been exposed to the risk of becoming a victim of human trafficking, or may have taken detrimental decisions due to lack of information.

When support is available, many outgoing migrants are unaware that support (e.g., centres) exists to support them.

Lessons learned

Strong links to communities with a high level of departing migrants increase the possibility to support them. If actors work closely, through other types of support, with communities where drivers to migrate are high, future migrants are more likely to learn about the services available to them.

However, behaviour change takes time, so long-term awareness programmes should be planned.

Common challenges

It is unclear whether migrants acquire necessary and relevant information from the support. For example, pre-departure orientation sessions are often designed to be one-size-fits-all. There is limited feedback from migrants on the usefulness of the training once they have left the country and put it to use.

Lessons learned

Monitoring and regulating training agencies is important to ensure trainings are of sufficient quality.

Common challenges

There are some concerns over which partners to work with. For example, private sector service providers may have conflicts of interest.

Lessons learned

The inclusion of civil society inputs is important. Additional partners can contribute by adding complementary perspectives, sources of information or services.

Common challenges

Some National Societies are wary of engaging in advocacy. They might not have acquired the human and technical capabilities to do so, and may be unsure of how to engage in constructive advocacy with their governments (without being perceived as being in open conflict with the government).

Lessons learned

Minimal support from the IFRC or a sister National Society can sometimes spur a National Society to engage in advocacy on migration. This can be done by providing a “license to advocate”. This empowers the National Society to advocate, by building technical capacity and sharing considerations on how to engage in constructive advocacy.

This requires a favourable political context.

Smart practices archive: Origin