Responses to migrants’ needs when they return to a country of origin

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

- This section considers the needs of vulnerable migrants who are returning to their country of origin. Needs are both short-term while travelling, and longer-term after arrival.

- First, migrants need regulatory safety; no individual is to be returned to a country in violation of the principle of non-refoulement.1 While travelling, physical needs such as safe shelter will be essential. Upon their return, migrants should have access to longer-term, sustainable support that seeks to redress the vulnerabilities and risks that posed a challenge in the first place. This might include access to employment opportunities, high quality natural capital, education opportunities, etc. Reunification with family in the country of origin is often extremely important, as family members will often help the returning migrant by providing shelter, food, and other types of support.

SMART PRACTICES

- Smart practices that were identified target financial and physical capitals, and education.

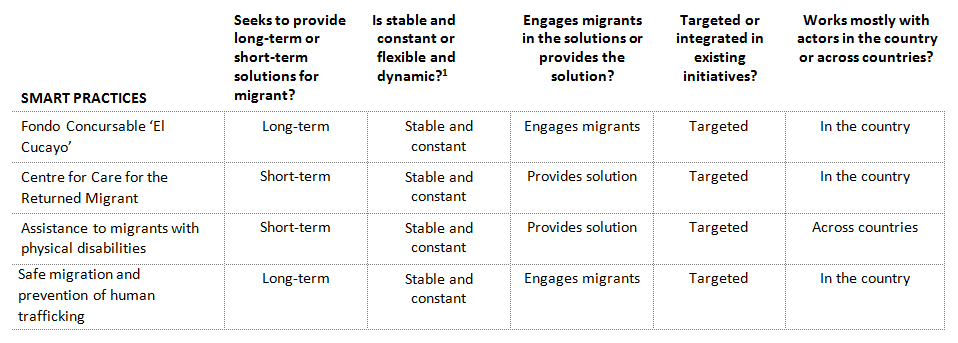

- The smart practices identified have several characteristics in common. Most seek to provide both long-term and short term solutions; are stable and constant; engage migrants in the solutions; are targeted; and work in partnership, mostly with actors in the country.

- When addressing the needs of migrants, actors have faced a number of common challenges. These include: difficulties to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of services, or provide all necessary services. Some lessons learned are: to work in full collaboration with partners, to leverage the skills and expertise of each, and to clearly understand the requirements, conditions and mechanisms for projects prior to starting.

1 The principle of non-refoulement prohibits the transfer of persons from one authority to another when there are substantial grounds to believe that the person would be in danger of being subjected to violations of certain fundamental rights. This is in particular recognized for torture and other forms of ill-treatment, arbitrary deprivation of life and persecution. The principle of non-refoulement is stated explicitly in international humanitarian law, international human rights law and refugee law, although with different scopes in each of these bodies of law. The spirit of the principle of non-refoulement has also become customary international law.

To remain resilient on their return, needs cut across all dimensions

This section considers the needs of vulnerable migrants who return to their country of origin. It considers migrants who are forced to return by a government, and migrants who return because they have not been able to make a livelihood in the country of destination or face other challenges. It does not consider migrants who voluntarily return with adequate savings, or migrants who voluntarily migrate home after a war. Support the latter might need in the country of origin would be considered under other types of support (e.g., economic development, reconstruction, etc.).

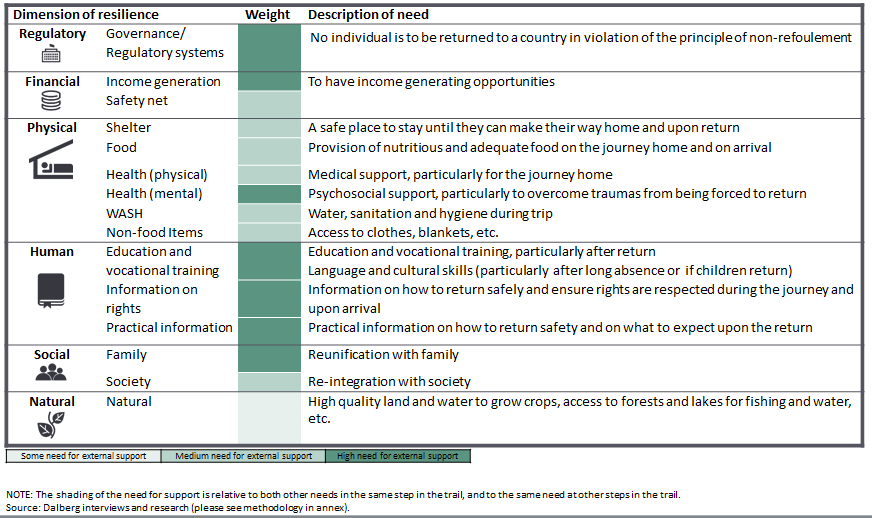

Governance/regulatory systems. No individual is to be returned to a country in violation of the principle of non-refoulement.

Financial capital. When migrants are forced to return (by force, because they have not been able to make a living, or because of another challenge), they will often be in a more vulnerable financial state than when they originally left. Typically, they will have spent a large amount of savings on the journey to the destination country and may not have been able to generate savings since the journey started. Moreover, they return to a country that many originally left for economic reasons. It is important that, on their return, they do not face similar economic pressures to leave and that income-generating opportunities are available.

Physical capital. While travelling, it is important that the migrant find safe places through which to transit, or at which to temporarily stay until s/he can make the final way home. During the trip, s/he will also need access to nutritious food, and water, sanitation and hygiene. Medical support may also be needed, as the migrant may have suffered on both the journey to and from their country of origin. Psychosocial support is often extremely important for the forced returnee, as she or he will often have risked tremendous amounts to make the journey, and return may feel like a failure. Lack of hope or similar feelings may be common.

Human capital. As a way to enable access to financial income, higher education and or vocational training might be important. Migrating children and youth might also need additional support to catch up on the months or years of missed education. They might also need to learn the language of their country of origin, or particular cultural habits. Finally, the migrant will need to have practical information on how to return safely and on what to expect upon return; and know his or her rights, to ensure that these are respected during the journey and on arrival.

Social capital. Reunification with family in the country of origin is extremely important, as family members will often help the returning migrant by providing shelter, food, and other types of support. However, re-integration with family and the society might not be straightforward, as the person might have changed, or the society might be critical of the person who left (e.g., if they were not able to make a fortune while migrating, or if they were forced into sexual work).

Natural capital. As discussed earlier, lack of natural capital might have been a driver for migrating in the first place; it is important that it does not become a reason for migrating again. Returned migrants may need high quality land and water to grow crops, or rely on forest or lakes for fishing, water, etc.

The table below provides a high-level summary of the common needs for external support that migrants may have. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for financial, physical and human capitals

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Sometimes migrants return to situations where they have limited opportunities for employment. Returned Honduran migrants said, “When we get back, we don’t get jobs, everyone think migrants are criminals,” and that, while there are some jobs, they are “only for a few hours or days, not enough to make a decent living or support a family.” Suggestions included more training and support for returned migrants to get jobs.

Moreover, the access to financial income of returned migrants can be reduced as a result of injuries experienced during the journey. Returned Honduran migrants highlighted that, once a migrant returns, he or she needs to find a job. However, if they have been severely injured (e.g., lost an arm or a leg) it becomes very difficult to take care of themselves, let alone work. They encouraged the establishment of agreements with companies to provide employment. “There is no better therapy to get your life back than to have a job and feel useful,” said one. Many people who suffer accidents decide not to go back and stay in Mexico because they do not want their families to have to support them, explained another.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Erroneous information on resettlement can lead to more vulnerable situations. Congolese migrants in Kenya explained that resettlement was sometimes erroneously communicated to people, who sold all their belongings and headed to the airport, only to find out that they were not on the list and that they had to restart from scratch.

Examples of the need for physical capital

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Access to health care on the way home was seen as a major need. Honduran migrants said that they had had different needs and experiences regarding access to health care on their return journey. For example, some had been treated in hospital before being deported, and been given a month to recover. Some had been deported by plane, others by bus. Those deported by plane explained that it was the preferred option, because they landed in a main city where it was easier to receive medical attention. One of the interviewees had been deported by bus within a few days of losing her legs. She had almost died on her way back, and then been left at the border of her country, far from medical services.

Some migrants feel a sense of failure when returning, which may turn into a sense of desperation if they were crippled during their journey. Honduran migrants also explained that “When you come back you feel like you have failed; and that’s when you come back safe and healthy. In addition some of us come back without an arm, a leg, or both legs, or sometime worse. You feel not only that you have failed, but that now you can´t do anything with your life.”

Some migrants are traumatized by the hardship and abuse they have suffered during their journey. The Honduran migrants confirmed that psychosocial support was necessary to overcome the hardship endured during the journey: “We need psychological support after we are back, some of us get raped or kidnapped, or saw our friends die. That’s not easy.”

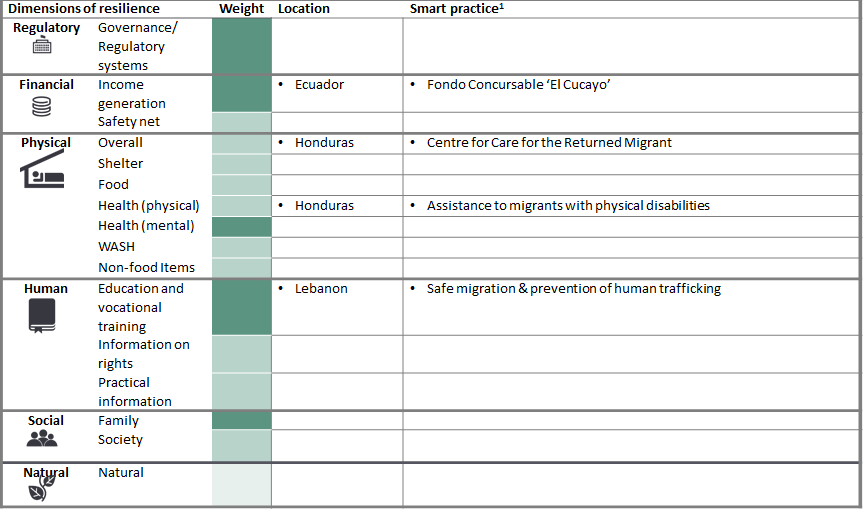

Smart practices identified target financial and physical capitals and education.

Smart practices identified at this stage are provided in the table below.

1. This is a living document; the IFRC will continue to identify and share smart practices, as National Societies and partners test, implement and scale up new initiatives.

Common characteristics of smart practices

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned*

Common challenges

Lessons learned 1

Common challenges

It can be difficult to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of services, particularly if they are provided along the returning route, as the migrant then ‘moves on’.

Lessons learned 1

Important to clearly understand the requirements, conditions and mechanisms for projects, and how they will be overseen, prior to starting.

Common challenges

It can be difficult for one organization to provide all the services migrants need, for example at a centre for returning migrants.

Lessons learned 1

Work in collaboration with partners to leverage the skills of each partner (e.g., one partner can provide healthcare, another psychosocial support, another information, another food, etc.)

* Challenges and lessons learned are from specific smart practices and from broader conversations with National Societies and other actors.

1 Lessons learned to address challenges may be from the smart practices that experienced the challenge or from other experiences Dalberg collected throughout the study.

Smart practices archive: Return