Responses to migrants’ needs when they arrive at the country of destination

Some migrants decide to regularize their status in the country. This section considers the period between a migrant’s arrival and the date on which s/he receives a decision on the petition to regularize his/her status. It presents an overview of the needs of migrants when they arrive in a country of destination and 10 smart practices that address some of their needs.

Key messages of this section

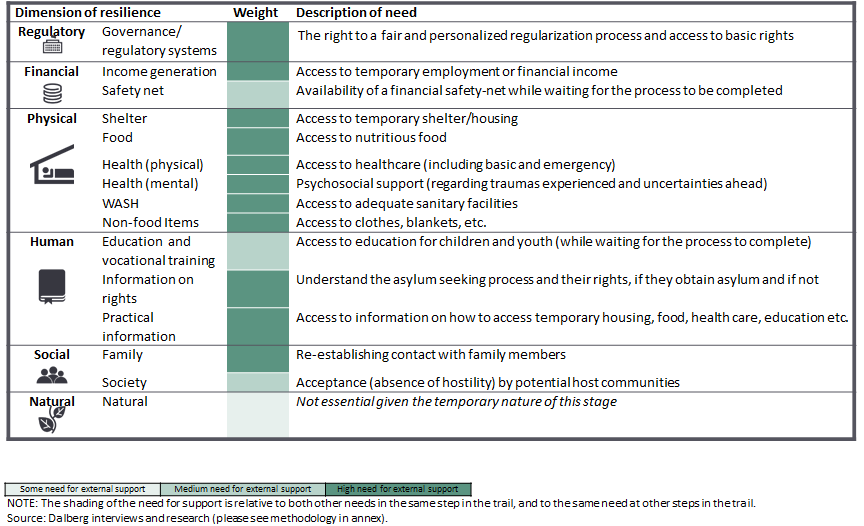

MIGRANTS’ NEEDS

- Needs include regulatory safety, basic physical needs, information, and family reunification. First and foremost, the migrant needs to be able to access a fair and personalized regularization process and access to basic rights. While a migrant awaits the decision, s/he will need access to all basic needs, even if most are of a temporary nature. Information on the asylum seeking process and rights are also extremely important at this point. The migrant can already seek to re-establish broken links with his/her family.

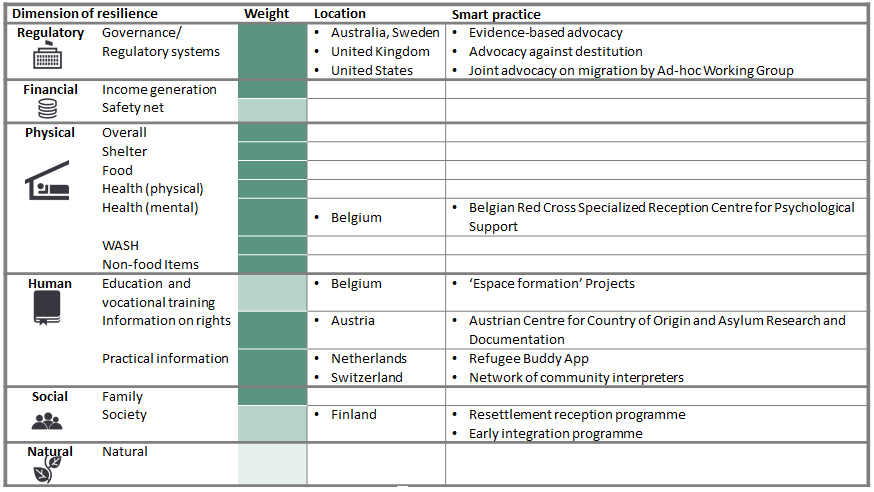

SMART PRACTICES

- Smart practices that were identified target regulation, information, health and integration in society.

- The smart practices identified have several characteristics in common. Most seek to provide both short-term and long-term solutions for migrants; are stable and constant; provide solutions for migrants; are targeted; and work in partnership, usually with actors in the country.

- When addressing the needs of migrants, actors have faced several common challenges. These include: overload of complex information, limited time to document evidence for advocacy purposes, and strong political stances that are not swayed by evidence. Some lessons learned are: to engage community interpreters when transmitting information, and, even if a political stance is strong, that evidence based advocacy can be a useful input for the government.

Needs focus on regulatory safety, basic physical needs, information and family reunification

This section is applicable to migrants seeking to regularize their situation in a country of destination. Depending on the country of origin and destination, this process can take from a few months to years. For example, in Germany the current average time from application to asylum decision is 5.3 months.1

Governance/regulatory systems. First and foremost, the migrant needs to be able to access a fair and personalized regularization process and access to basic rights.

Financial capital. Because the waiting period can last several months, if not years, it is important that s/he can have access to financial income. It is, however, very rare that migrants waiting for a regularization decision are allowed to engage in any work.

Physical capital. While a migrant awaits the decision, s/he will need access to all basic needs, even if most are of temporary nature. For example, s/he will need access to temporary shelter/housing, nutritious food, healthcare, and adequate sanitary facilities. Moreover, psychosocial support is often needed to help overcome traumas experienced in the country of origin or the fear of an uncertain future.

Human capital. Information is extremely important at this point, as the migrant needs information on the asylum seeking process and his/her rights. The migrant should have a good understanding of the process, the estimated timeframe before s/he can expect an answer, the likelihood of receiving a positive answer, what rights s/he will have if s/he obtains asylum and what will happen to him/her and his/her family, if not. Practical information on how to access temporary housing, food, health care, education, etc. is equally vital, as s/he can seldom access them through ordinary ways. Minors are at particularly high risk of suffering gaps in their education at this stage, particularly if the process takes several months. Access to education for both children and youth while they wait for regularization is therefore essential.

Social capital. While migrants may not be able to reunite with their families at this stage, they can already seek to re-establish broken links with them (if they have not been able to do so earlier). While integration within the host community is not yet guaranteed, acceptance by potential host communities helps migrants to overcome remaining challenges, and can assist future integration.

Natural capital. The need for natural capital is not essential while the person is waiting for a decision, given the temporary nature of this stage.

The table below provides a high-level summary of the common needs for external support that migrants may have. While all areas are likely to need support, a darker colour indicates a generally higher need for external support.

Examples of the need for regulatory safety, human (information) and social (family) capital

HONDURAN MIGRANTS, HONDURAS

Where possible, migrants access information from friends and relatives with relevant experience. Honduran returned migrants explained that they had had some information about their rights, but not all the information they needed. They explained that they knew they were breaking the law and had an idea that if they got caught they would, for example, be thrown in jail in the US for 3-7 months and then be deported. “We all know about the risks of the trail, but we think they might not happen to us, or we are willing to take them. We also know that out of 10 only one makes it.” This information was mostly gathered by word of mouth, from those who had already migrated (and returned).

SOMALI MIGRANTS, KENYA

Being irregular results in a sense of insecurity for many migrants. Somalian urban migrants explained that the main issue for them is “obtaining alien cards and the associated respect”. Having no documents implies a constant threat of being detained. “The thing we need most is to feel secure,” they explained.

SYRIAN MIGRANTS, TURKEY

In some situations, some migrants are ‘regularized’ directly. In Turkey, all Syrian migrants automatically have the right to stay, indefinitely as ‘guests’. Moreover, they have the right to education, health care, etc.

CONGOLESE MIGRANTS, KENYA

Sometimes families do not get the same status. Congolese migrants shared some personal stories on how different members of a family had obtained different status.

- A Congolese man in Nairobi since 2007: His first wife was abducted by rebel forces and he does not know what happened to her. His second wife is with him in Nairobi with his three children from his first wife and his three children from his second wife. His wife and children have regularized status but, for some reason, he has not obtained this status.

- A Congolese man in Nairobi since 2001: He followed his wife and eight children a few days later but they have not been recognized as one family. The rest of the family received status but he has not. He has been waiting for family reunification to become official since 2001. There was recently, some recognition of his case, which may result in some progress in July 2016.

ASYLUM SEEKERS, SWEDEN

Some migrants may not be regularized because they fear or misunderstand the asylum process. An interviewee who works with unaccompanied minors in Sweden explained that a key challenge she had witnessed was fear and misunderstanding of the asylum process. She explained that there were so many rumours, stories and misunderstandings that people sometimes did not dare to tell their stories, which would have helped them obtain asylum.

Source: Dalberg interviews with migrants through focus groups conducted during country visits, and phone interviews with service providers in the country.

Smart practices identified target regulation, information, health and integration in society

Smart practices identified at this stage are provided in the table below.

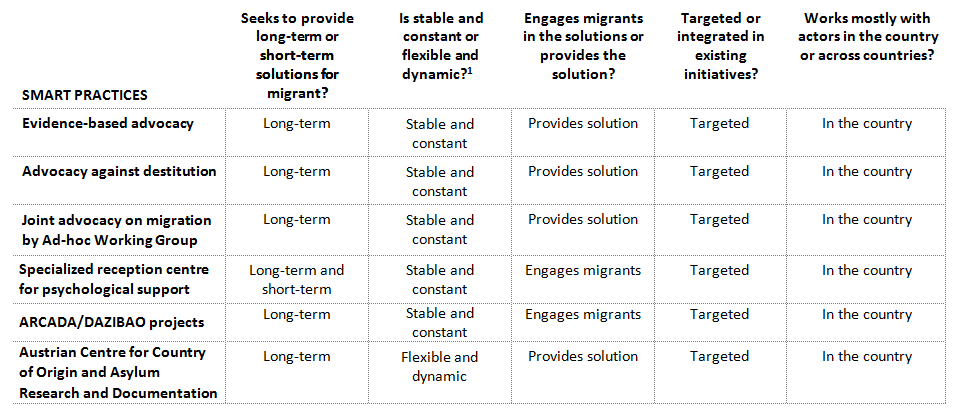

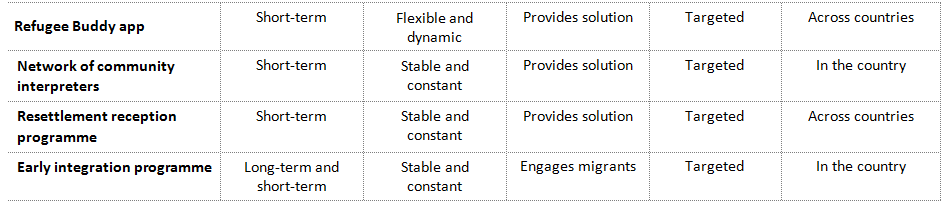

Common characteristics of smart practices

The smart practices identified have several common characteristics. Most seek to provide both short-term and long-term solutions for migrants, with the vision that migrants may remain for several years; are stable and constant, but flexible enough to adapt to the specific needs of migrants; provide solutions for migrants; are targeted; and work in partnership, usually with actors in the country, although some exceptions apply.

- Refers to whether target beneficiaries, services provided, or periods or locations of provision, are subject to change or remain constant and predictable.

Common challenges and lessons learned

Common challenges

Lessons learned

Common challenges

Volunteers and staff have to deal with complex information on the one side and very detailed questions from migrants on the other.

Lessons learned

Community interpreters can support in transmitting the information. They can thus help ensure equality of treatment and protection against discrimination, and increase the efficiency of public services for migrants.

Common challenges

It can be difficult to ensure that evidence is properly documented by overburdened staff or volunteers, which can hamper evidence-based advocacy.

Lessons learned

Evidence collection and advocacy should be embedded in programming and staffing at all levels.

Common challenges

There are some concerns over which partners to work with. For example, private sector service providers may have conflicts of interest.

Lessons learned

The inclusion of civil society inputs is important. Additional partners can contribute by adding complementary perspectives, sources of information or services.

Common challenges

Strong government stances on an issue can mean evidence-based advocacy is ignored because the government decision may be political and hard to sway using factual arguments.

Lessons learned

Despite strong political stances, some governments are appreciative of an evidence based approach to advocacy and see it as a way to keep the government updated on reality.

A collaborative approach with the sector and key government departments is key to change.

Harnessing the power of the Red Cross Red Crescent brand can be used to advocate for change.

Using clear evidence of the humanitarian problem together with a focused solution is an effective strategy.

1 Challenges and lessons learned are from specific smart practices and from broader conversations with National Societies and other actors.

2 Lessons learned to address challenges may be from the smart practices that experienced the challenge or from other experiences Dalberg collected throughout the study.

Smart practices archive: Arrival